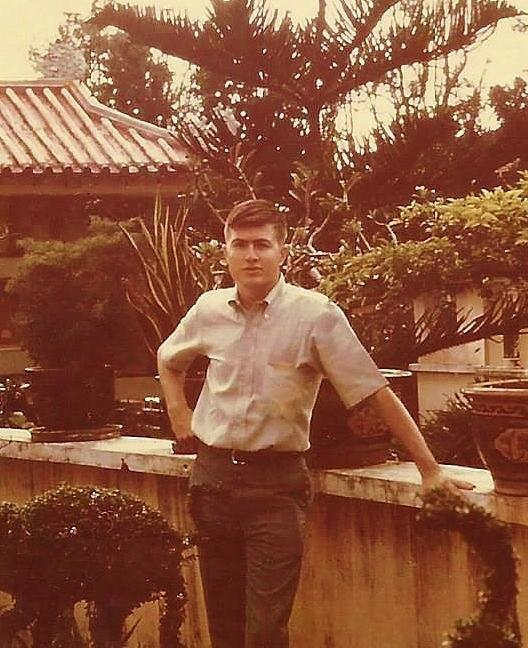

Author's Name: Thomas Griggs

Title: "Moon Over Saigon"

It was during my second tour of duty in the Vietnam War, when America's deputy ambassador to South Vietnam popped into my room and asked me if I wanted to watch the television coverage of the moon landing.He was talking about the first moon landing, the "giant leap for mankind" moon landing. The historic event took place at 4:17 p.m. Eastern Daylight Time on Sunday, July 20, 1969. It was 3:17 p.m. on clocks in the St. Louis area, where my family and friends back home would have been watching it. That would make it already 3:17 a.m., July 21, Saigon time, when Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin landed on the surface of the Earth's moon.

Deputy U.S. Ambassador Samuel Berger had not stopped by my room at Marine House No. 1, which was the name for one of two dorm-type barracks for the embassy Marines in Saigon. He was standing in the Marine security guard room – or office, you could say – on the second floor of the ambassador's home in a residential neighborhood in Saigon's 3rd Precinct.

"You want to watch the moon landing, Cpl. Griggs?" he asked. Maybe that's not exactly how he put it. It was a long time ago, and my brain's memory compartment is a little cluttered.

"Yes, sir!" I answered. I'm pretty sure I said at least that much.

Speaking of memory, I've often heard people ask others if they remember where they were when Armstrong set foot on the lunar surface. I, of course, recall my night watching the historic milestone alongside Ambassador Berger, but I now realize that we probably weren't watching it live, with the 600 million viewers around the world who did.

American Forces Radio and Television Service in Vietnam, better known as American Forces Vietnam Network or AFVN, aired it delayed rather than live. It was recorded in the Philippines and flown by jet aircraft to Saigon and played the day after the actual event.

The ambassador's television was located in an upstairs room next to the Marine guard room, at the top of the big staircase in the French colonial-style home. That's how I remember the house, but I've already told you about my dubious memory recall. Still, I think that's pretty accurate.

As the Marine on post that night at the Berger residence, I was supposed to be the ambassador's body guard, not his special guest for a TV screening of lunar history being made. However, I figured, how better to be able to protect the ambassador than to be sitting just several feet away, with my Smith and Wesson .38-caliber pistol and my fully automatic M16 rifle?

South Vietnamese soldiers and police guarded the exterior of the residence, as usual, and I was at the ready on the inside, as always. And there I was, sitting in the same room with the second most powerful American diplomat in Vietnam, ready to watch coverage of space-exploration history. It was all a bit surreal.

The most incredible part was witnessing those first steps on the surface of the moon. It was so astounding, practically beyond belief. How could it be? But it was. I was mesmerized. Viet Cong terrorists could have lurched into the room, and I would have blasted them to obliteration, not just to protect the ambassador but because they would have interrupted the greatest show on and beyond Earth.

That's pretty much how they billed the first moon landing – the greatest show ever. A fifth of the people on Earth watched it live. I was in awe watching the recorded images the next day. Remarkable.

Almost everyone on Earth today probably knows the famous words voiced by Armstrong as he stepped onto the moon: "That's one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind." I always think about how more politically correct it could have been if Armstrong had said "humankind" instead of "mankind." But the accomplishment was so monumental and phenomenal that I guess even the equal-rights folks didn't mind.

Perhaps the best observation about Armstrong's famous statement came from Sir Edmund Hillary, a great adventurer in his own right. Remarked Sir Edmund: "Better if he had said something natural like, "Jesus, here we are.'"

Aldrin joined Armstrong on the moon's surface, where they spent 21 hours before reboarding the lunar module Eagle with 46 pounds of moon rocks. They blasted off and returned to the command module Columbia, which had been orbiting the moon, piloted by Michael Collins. It was all such stuff of science fiction before 1969, and it still seemed so in a way, because it was so unbelievable. Again, remarkable.

The awe and inspiration stuck around for awhile, but things soon got back to normal in Saigon. Two months after the moon landing – almost to the day – Viet Cong terrorists bombed a Vietnamese government vehicle on Nguyen Thong Street, just a block from the Berger residence. About 25 minutes later, in the same neighborhood, insurgents blew up a U.S. Navy truck right outside a Navy building.

By then, I had been promoted to sergeant and assigned to the Saigon Marines' radio network, to work as a communicator in the embassy with three other sergeants. I'd no longer get to stand post at the Berger residence, but I liked my new job.

I did, however, get to stand post again, when I volunteered for extra duty as a Marine security guard for a few days at the Abraham Lincoln Library in Saigon. Remember those 46 pounds of lunar rocks the astronauts collected? Some of them were brought to Saigon to be displayed briefly at the library. Guard moon rocks? You didn't have to ask me twice. I was on board. Rocks from the moon! Once again, remarkable.