Author's Name: R.D. Puller

Title: "Cold War/Hot War"

My war was as different and alike as any other soldier who served during the Cold War, and in the Hot War, Vietnam. It matters quite a bit whether a soldier was a rifleman, or chopper pilot, or gun-bunny, or a forward observer, for instance. Most U.S. Army personnel, myself included, logged the bulk of their time behind the wire, in base camps, or on firebases in support of those down range, slogging and slugging it out with the VC, or NVA. As a "rear-echelon-mother****er", my memories mostly relate to the atmospherics of that time from a partial remove (though on occasion, the war could get up-close and personal, downright sporty). A rough estimate of how I might (looking back) quantify my day-to-day Vietnam experience:

-> 50% routine/wearisome

-> 35% interesting/fun

-> 15% nasty/anxious/fearful.

*Other veterans, especially grunts, would have a very different calculus.

Rabbit Hole: 1,2,3

In early 1968 I received a letter from my draft board letting me know that I was going to be drafted on or about my nineteenth birthday, so I enlisted a few months earlier. Basic Training at Fort Leonard Wood was like going down a rabbit hole into an alternate existence, swallowed by the big green machine. That was a momentous year1968 (the most deadly year for Americans in Vietnam): the Tet Offensive, MLK assassination and riots, LBJ dropping from the presidential race, the Chicago Democratic Convention and riots, RFK assassination, Nixon elected, the Paris riots (& world-wide student uprisings), and the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia. These events impacted my generation hugely.

I was one lucky rabbit, however. Trained as an artillery surveyor at Fort Sill, Oklahoma after Basic I got orders for USAEUR. Sent to West Germany, I was assigned to the 3rd Armored Division, HQ in Frankfurt, arriving there in mid-September. Having good test scores (& typing skills to boot) a staff sergeant in the replacement company pulled me out of line and assigned me to the HQ Company, where I worked in Division G1 and G2. It was great duty there at Drake Kaserne where I learned a little about the army, was able to mature, gain some rank, travel, and experience the Cold War realities as existed in Western Europe. Most of the guys in HQ were college grads and had avoided Vietnam. A few GIs ended up in my unit after serving in Vietnam. They were cool, and a bit distant, saw duty in West Germany as plush, which it was. Yet the Cold War was full freeze in 1968-69.

The 3rd Herd (nickname) was George Patton’s old division, became part of NATO forces after WWII. Our armored and mechanized brigades were the forward Spearhead Division spread across the Fulda Gap protecting Western Europe along the Czech and East German frontiers. Our mission was to act as a deterrent (& stop-gap) against invasion from the Warsaw Pact armies.

The Soviets were very frisky in those years, taking advantage of the American preoccupation in Southeast Asia. In August 1968, just three weeks before I reported to West Germany, the Kremlin sent 800,000 Warsaw Pact troops and armor into Czechoslovakia, centered on Prague in an effort to put down a liberal reform movement begun earlier that year under Czech leader Alexander Dubcek. Soviet forces (with the KGB & Czech Commissars) strangled democratic dissent, shutting down the Prague Spring.

In the Fulda Gap, the 3rd Armored Division stayed on high alert for the next six months (we were quietly briefed that our forces were expected to delay the Red Army by all of twelve minutes before being obliterated should `the balloon’ go up). It was a scarier Cold War than most civilians knew (the most tense since the Bay of Pigs, Berlin Wall, and Cuban Missile Crisis, back in 1961-62).

A year and a half later I was ordered to Vietnam, along with a good friend, O’Rourke. Our 1st Sgt. gave us a week’s leave. We went to London, had a great time. Back in Frankfurt, our pals gave us a good party (like a wake) and we left send-off from Europe. I spent Xmas 1969 at home (St. Louis region) then to Fort Lewis, WA. A week of RVN training in the rain and damp: weapons, tactics, radio, maps, latest Nam political/social intelligence, etc. Got a bad ear infection that dogged me for weeks, made worse in Vietnam (along w/ big explosions, & loud rock `n roll has left me a legacy of tinnitus ever since).

My first week in Vietnam, (at Long Binh, outside Saigon) was spent in a hospital ward where enemy rocket blasts plopped periodically. From there I was assigned up-country, to the Central Highlands. In 1970, to the armchair boys in Saigon & Long Binh, the Highlands were viewed as exotic, dangerous, and wild; the primordial boonies where bronze-age hunter-gatherers still roamed (some believed as headhunters). More training, a few day patrols (led by experienced short-timer grunts waiting for orders home). One over-nighter to a near-by firebase we forded a stream, got leaches, entered a `Montagnard’ village (French for `people of the mountain]. These were the `bronze-age’ indigenous natives of the Highlands. NOT headhunters, though they hated the VC and made the best army scouts. They followed us for hours, (even the women and children) trading goods with us when we took breaks in the shade. I recall trading C-ration cigarettes for a woven bracelet.

Time (when) and place (where) mattered greatly as to the nature of the war you found. My when: 1970. My where: II Corps, Central Highlands, to the 4th Infantry Division. The HQ was Camp Enari, near Pleiku, (in the shadow of Dragon Mountain). Around Easter, 4th Infantry moved east to An Khe (in the shadow of Hon Cong Mountain) part of the Vietnamization phase, turning over bases to the ARVN soldiers in the slow withdrawal of American forces from the region. I left Vietnam, along with the 4th Infantry, who were redeployed to Fort Carson at the end of 1970.

A Brief Roll Call: Dots, Dashes, Flashes, & Bits:

• Central Highlands was an interesting and varied terrain. Plains, mountains, rivers, jungle (w/ double & triple canopy. Beautiful sunrises & sunsets. Cool many nights. Monsoon intense.

• On the bunker line, guard duty in the highlands you could see the stars, the far horizons, Puff the Magic Dragon, Cobra gunships working out, mini-guns (every fifth round a tracer); Arc Lights (B52 bombers) toward Cambodia, ground rumbling all the way to the Ho Chi Minh trail.

• Lot’s of critters: saw a tiger once, from the bunker line at sunset, at the edge of woods, about 800 meters out, through a scope; even at that distance the hair at my nape stood on end. On another night, a tiger was sighted behind the wire (in the perimeter). We were very awake.

• Coming down a company road with some buddies at sunset we found a soldier who had been jogging in a seizure. He had been bitten by a king cobra (we heard later from a nurse). We got him to the base hospital, where he died later. Nurse said that his jogging (blood pumping) doomed him. Some guys beat the bushes, caught the snake (maybe a different one?) and tacked it to the side of the poor guy’s hooch (a 6-7 footer, a head w/ hood the size of a skillet).

• Awoke one morning to a blood-curdling scream from a hooch down the way. Bunch of us ran down there to find a soldier cussing and shaking. He woke up to find a baby mongoose curled around his neck like a muffler (it had been a cool night). His bunky chased the little mammal out the door. After the cobra incident, we were all in favor of mongooses (mongeese?)

• Another morning, getting dressed, a buddy in my hooch let out with a high-pitched scream, startling everyone; I even grabbed my K-bar, thinking VC sapper, or a big-ass snake. It was a millipede the size of a Tonka truck. It had skittered up his bare foot heading north. He felt, he said, every little nasty foot on his bare flesh before he slapped it off. I saw the freaky thing; spotted, milky white, w/ a shiny-hard carapace (as if a 9lb. hammer might bounce off it).

• Critters gave us the willies because they were so alien. Even the dogs of VN were strange, wild Dingo more than dog. GIs protected them; believing the poor locals would eat them.

• Killed a small snake one night in a forward listening post. Gave it a butt-stroke w/ my weapon, tossed it outside. Next morning, the Sgt. Of the Guard said it good that I killed the reptile b/c it was a pit viper, very deadly. My 20 yr. old stupid self wore the carcass like a headband around my helmet for a few days until my Sgt. told me to get rid of the stinky thing.

• Every plant and critter seemed toxic, or at least hostile, if not rude. Even the monkeys, especially when drunk, they could be either affectionate, or mean, screechy little bastards. Some GIs took them as pets, but they were fickle, came and went as they pleased.

• Some guys collected scorpions and/or rhinoceros beetles. They held competitions and bet on the fastest, or fought them like gladiators. Had to check boots & clothes every morn, especially for scorpions, or spiders.

• Lizards made good pets. Some were called, F/U Lizards (b/c that expletive was the sound they croaked). We told Newbies the F***You’s they heard were taunts from the VC out in the bush.

• The war came intruding via mortar & rocket attacks. And sappers that penetrated the wire to blow shit up. The worst month for my unit, was in April, then later in September at An Khe, (Camp Radcliffe at the base of Hon Cong Mt.):

• Red alerts constantly; the worst night a cadre of sappers came through our A/O. The target was the helicopter pad nearby. They did a good deal of chopper damage. On their egress they destroyed a few of our buildings (including the shower-room where one of our men saw a dark hand drop a small canister through an open window. On blind instinct he hit the deck just as the shack blew-up. We found him dazed under the debris shivering, his backside full of splinters, covered in grit and smoke, ears bleeding; but mostly unharmed, he returned to duty later that week, ears still humming).

• The sappers had egressed through our Company and a bunch of us volunteered to join the grunts. We suited-up, grabbed our weapons and went up Hon Cong (which was constantly exfoliated by chemicals) but they got away through the outer wire (tunnels no doubt). The only one we saw was in pieces, blown up (either by mistake, or was wounded & offed himself).

• VC Sappers were very dangerous, dedicated, and elusive. At Pleiku, in training, we saw a Chu Hoi sapper demonstrate how quickly, how silently, (w/ a pair of sticks) he could infiltrate the wire, despite claymores, rattles, tripwires, foo-gas, and flares. It amazed, and sobered us.

• One day I came back from the mess hall to find Woody, a buddy, convulsing in his bunk (with malaria). We got him to the army doctors where they packed him in ice to bring down his temp. In a medevac to Japan he died. A month after R&R in Bangkok, just a few weeks before my DEROS, I came down with a touch of malaria. Sweats, fever-dreams, lost weight (down to 125lbs.). Lucky bunny me, it was not the recurring malaria that plagues many still.

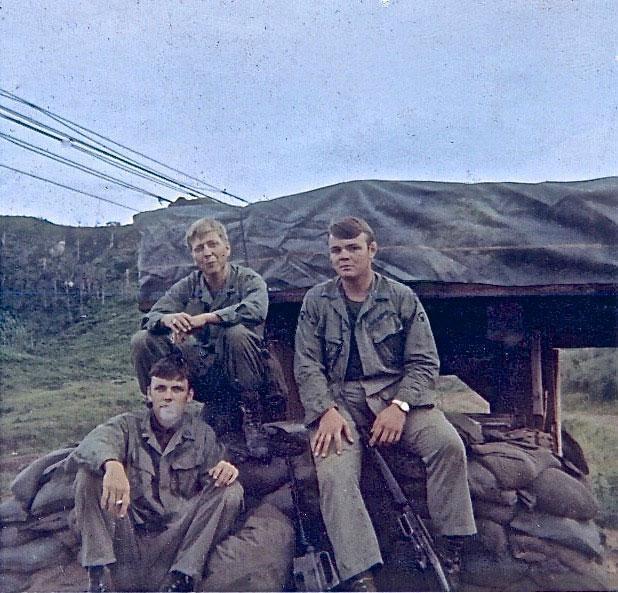

• Hometown buddy, Tommy Hudson visited me on in-country leave. Storms kept him in An Khe for 5 days. He was a machine-gunner, had been in Cambodia where he was blown off his APC. His back and shoulder still hurt, minor shrapnel that he dismissed with a smile. We had a good time together, before he went south to a new unit in IV Corps. He never made it home.

• Tommy was killed just four weeks after I came home. The last known photo of Tom was taken there, in An Khe, at the EM Club. It shows us together, smiling big for the camera in the garish light of the bar, leaning shoulder-to-shoulder forever young. I gave his sister has that photo. Will never forget how she wept when I told her of our time there in those fading days of war.

Aftermath, Civilian 2.0

I remember those wobbly early days after coming home. Entering a household, a party, a classroom, or a family get-together. Uncertain with this terrain, and how quickly the group dynamics might alter; I check sight lines, doors, windows, the exits. Some people fall silent, conversations change, eyes avert, traces of panic (in me or them?). I seek the first opportunity to slip out back, Jack. Ignore invitations like a gloomy Gus.

Being out of the country for close to two and a half years, America had become a different country, so many changes between 1968 and 1971. I had to learn my country, my place in it after Vietnam. Other veterans report same-same, the difficulty catching up to peers, assimilating back to civilian life in those re-entry weeks, months, and years. We vets were visible reminders of a misbegotten and tragic era. America did not want to be constantly reminded of Vietnam and the divisions that arose in the aftermath.

Many of us internalized these attitudes and recoiled into ourselves. Some of us felt an inner contempt and grew ashamed for our service. Some vets fought against the role as a scapegoat for Vietnam. Speaking for myself, I did both. Many days on autopilot, drifting away `on the thin ice of a new day’. Some days bereft of any self-worth, or clarity of mission, desperate for a new identity, lost, `reeling in the years’. Other times, the chip on my shoulder was the size of a 105 howitzer, my attitude locked and loaded, rejecting the rejection of my country and crass materialism and culture of the 1970s-80s. I went to college on the GI Bill to find answers, to seek a bit of honey, or redemption; and learn more about history, philosophy, literature, art, music, and politics.

Most of the vets I hung with after Vietnam were clannish, like members of a secret club. In the club we could open-up and talk about our experiences. Or we could talk about nothing much at all. In shorthand patois we could finish each other’s sentences, spill our guts to great depth, be bellicose in false bravado and swap lies like mountain men at rendezvous. Our patient loved ones and friends helped us to be less fidgety, or less clenched (like a fist). When together, veterans did not have to pose, or posture, or be ashamed, or reduced to a stereotype. In these ways we help each other let it (the baggage) go, or keep it (sanity) together. And to remember that, `it ain’t nothin’ but a thing, man!’

Conclusion

Many Americans were either ashamed, or outraged about the conduct and outcome of the war. After the Fall of Saigon in 1975, as the nation tuned out, or shut it off, the war was no longer relevant, at least on the surface. I tried to tune it out, shut it off, and mostly that worked. Within a few years most of the new people I met, went to school with, or worked with had no idea I was a Vietnam veteran. It seemed no longer relevant. For the veteran, war is always relevant because it never leaves the marrow. It resides within us, lurks at the edges of our thoughts, in our staccato memories that enter and leave like sappers. The war quirks our choices, alerts us to any uncertain stimuli and shades our responses.

Vietnam veterans are as unalike as we are alike. We share many of the same political, historical, and cultural touchstones. Like veterans of all wars in history we tend to avoid talking about our experiences even to our family and friends, or others who did serve. Many of us are still bruised, even haunted by Vietnam. And not just by the war experiences, over there. The re-introduction back into `the world’, for many of us, added insult to injury as the country, more or less, turned away from us in shame. We were stereotyped, branded as maladaptive misfits, as a social burden. Most veterans (those still with us) have learned to roll with it. Each of us, in own way, adapted over the years, and long ago come to terms with Vietnam. Sadly, America has not. Gustave Flaubert wrote, “ Our ignorance of history makes us libel our own time.” I believe this is especially true in America.

As a historian and retired history teacher, I am haunted by the depth, breadth, and poignancy of our past. Historically, this country carries great sorrows, has perpetrated great crimes along with the glory and triumph of democracy. As the writer, James Baldwin wrote, “People are trapped in history. And history [tragically] is trapped in them.” As such, Vietnam has been festering for fifty years and a wound in America and Vietnam that has yet to heal.

I do not blame (and never have) the war protesters, draft-dodgers, the news media, the SDS, hippies, the silent majority, (or even Jane Fonda) for the loss of Vietnam. I was in Vietnam during the secret bombing campaigns, the invasion of Cambodia, and the killing of students at Kent State. By 1970 most of the soldiers in Vietnam, had long figured out: the war was wrong, all wrong from every angle. There was dissension within the ranks (by age), between career lifers and us short-timers; yet all us knew that there was duplicity and cover-up from the highest levels down to the platoons, that our leaders were `cooking the books’, (bogus body counts, for example) and nothing quite squared. *See the Pentagon Papers.

There are many to blame for Vietnam (and the Iraq War). Round up the usual suspects!

Our citizenry might learn what truth can be learned and apply those truths to future actions. My hope that the new documentary (by Ken Burns & Lynn Novick) will be an close examination of the war (primary sources are best) and that those years and decisions made by our leaders will be seen more fully in context, and that the nation learns from it. And, that the film will act as balm, or an elixir to heal this country and the people of Vietnam.

~R.D. Puller

St. Louis, MO.

Sept. 18, 2017