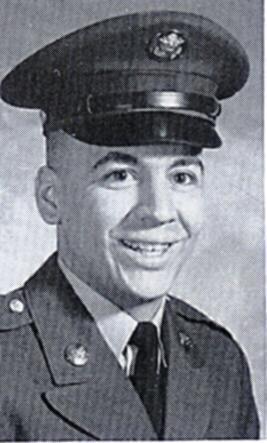

Author's Name: John Samuel Tieman, Ph. D.

Title: "My War as a Clarinetist"

“One time, the band played a welcoming ceremony for these grunts – and I mean they walked right out of the bush and into “Stars and Stripes Forever.”John Samuel Tieman, Specialist 4th Class

in country from June to December of 1970

02J20, CLARINET was my Military Occupational Specialty. As an artist, I served my country. Beyond that, I did nothing either heroic or noteworthy. In truth, I’m a far better veteran than I ever was a soldier. And that’s how you know I’m really a war veteran. That I’m not a wanna-be. Nobody ever lies about being an Army clarinetist. They lie about being a scuba-diving Green Beret ninja, who flew a B-52 before joining the SAS Foreign Legion Marines.

I volunteered on February 17, 1969, and after Basic at Fort Polk, La., I was stationed at Fort Wolters in Texas with the 328th Army Band. I was a parade soldier, a specialist 4, who also loved playing first-chair clarinet in a 30-piece orchestra.

Being stationed in the States wasn’t bad. Frankly, we were the envy of many—such as the time we played this gig at the Fort Worth Home For Unwed Mothers. Nothing happened—not that we let the guys back at the base think otherwise. Of such are legends born.

By 1970, with less than a year to serve, I never thought I’d go to Vietnam. Then came the Cambodian invasion. For 174 days, 1 hour and 22 minutes, I was stationed at the 4th Infantry Division’s base camp, Camp Radcliff, at An Khe in the Central Highlands, in the Division Band. In those 174 days, we saw more than 100 rocket and sapper attacks. Some nights, Charlie would lob a rocket in just to keep us awake. One night, sappers blew up 17 helicopters.

The band members’ central functions were as artist and guard. During a Red Alert, we served as guards for the headquarters company. At other times, we functioned as perimeter guards, generally assigned to either a tower or a foxhole.

A typical day started shortly after dawn. We might do a “police call” or a “sweep” to try to flush out sappers who were still hiding in camp after the previous night’s attack. The band would usually play a job during the day, an awards ceremony for example. If we performed outside of camp, we might take a Chinook to someplace like Nha Trang. Or we might join a convoy going east through the An Khe Pass or west through the Mang Yang Pass.

I hated the Mang Yang Pass. I hated how steep the sides were, how narrow the road was. When we entered, we had to pass “The Frenchmen’s Graveyard,” the last resting place of Groupement Mobile No. 100. It was wiped out in June 1954, right where we were driving in June of 1970.

In the evening, we might pull guard duty. On average, I stood duty every third night, but toward the end of my tour, it was every other night. Any soldier who has pulled guard duty in a combat zone can tell you how it ranges from the boredom of staring at the field in front of you, to the shock of hearing an explosion behind you. Some of my most vivid memories are of guard duty. An explosion over my shoulder. The Red Alert siren. Knowing a sapper must be right there somewhere, but having no idea where.

Like other soldiers, our band members found themselves assigned to all manner of general duty, from filling sandbags to painting artillery shells, from cleaning rifles to repairing the hooch.

But, aside from these combat duties, our primary purpose was to provide music. From the ancient Romans to Army bands deployed to Iraq, music has been used to signal, to encourage, to entertain and to comfort.

Our gigs could range from the prosaic to the exotic. Our band covered the entire II Corps Tactical Zone, and we got around.

On the prosaic side, we played change-of-command ceremonies. Most of these I’ve long forgotten. But a few I remember, like the time we played for a firebase so small that we had to set up in the surrounding minefield. I still remember that little red flag by my left front. That and someone pointing to a clump of trees and mentioning the Viet Cong “sniper last night.” Forty years later, I can close my eyes and still see that clump of jungle.

Then there was the exotic. Like the night we played at a party for the “Dragon Lady,” the wife of the province chief, a beautiful woman dressed in tailored, tiger-striped fatigues. She commanded an all-female unit. For that gig, we convoyed through the Mang Yang Pass to someplace near Pleiku. We played one song and spent the night in an old Foreign Legion barracks. The decadence of such gigs was never lost on us.

Our piano player, PFC Dick Bittner, used to refer to these scenes as “cartoons.” One time we played a welcoming ceremony for these grunts walking into the base camp—and I mean they came right out of the bush and into “Stars and Stripes Forever.”

Speaking of decadence, I’d be less than candid if I didn’t say that many of us comforted ourselves with drugs, alcohol and prostitutes. Such was life as an Army clarinetist at Camp Radcliff. Only years later did it strike me as paradoxical that I would go to a supply bunker and requisition a bandoleer and a box of reeds.

I got out of Vietnam, and the Army, on December 7, 1970. I was 20 years old. I rarely played music after coming home. A source of joy, the clarinet, had became a source for traumatic memory.

—

Copyright 2010 John Samuel Tieman. First published in HistoryNet. Republished by permission of the author.