Author's Name: Jim Stettler

Title: "Finally Welcomed Home"

As I write this, it has been 45 years since my return from Vietnam serving in the U.S. Army. I never bothered to write any of this down in the past, but now that I am retired, I felt the need to document my thoughts before I forget it all as I approach the inevitable path of old age. The one thing that has changed noticeably for the better is the respect shown, and the way we treat our active military service members, along with veterans; but it wasn’t always that way. For more than 40 years, my military service has not made me feel like part of any openly cohesive group, such as a college alumni association or the Rotary Club. Nor have I joined the American Legion or VFW or proudly acknowledged that I was a Vietnam veteran. I didn’t deny it, but I didn’t flaunt it either. For a long time, nobody wanted to be reminded of that period in our country’s history.I Got to Thinking

Most people have some special dates that they remember. Some may be celebrated year after year, such as a birthday, wedding anniversary, or the first time you met your spouse.

There are also those defining events where everyone remembers exactly where they were when it occurred. If you’re as old as me you remember exactly where you were when you heard the news that President John F. Kennedy was assassinated (1963), or when U.S. astronauts landed on the moon (1969), or when the Space Shuttle Challenger exploded shortly after liftoff (1986), or when you heard about the Islamic terrorists crashing the planes into the World Trade Towers (on 9/11/2001). In each case, there was an instant of disbelief as you were overwhelmed with the perceived implausible reality of it all. The events highlighted above are probably common to anyone who is old enough to experience them. In a lifetime, I suspect that the average person has less than twelve of these shocking events of a lifetime that we can all share.

Currently, there is a public discussion on how best we should commemorate the 50th anniversary of the lunar landing on July 22, 1969. It made me remember that I was at a co-worker’s house when we watched the whole event live as it occurred; that is if you are not one of the nuts that believed it was a conspiracy and all staged on a secret Hollywood set somewhere to trick the American public.

But there are also events that you have chosen to remember that are special to you and probably no one else shares. I was sitting in the IKEA store restaurant in Houston on July 21 of this year when my wife noticed that the old guy sitting next to me had a Vietnam Veteran T-shirt on. (I’m an old guy too, but he was older, and I confirmed it later.) She quietly pointed it out to me and I eventually asked him where he served in Vietnam and the year he was there. He told me he was there in 1966 and served in the Navy on a supply ship providing logistical support to the troops on shore. I mentioned that I served in the U.S. Army in DaNang in 1971 and that, by coincidence, I had left the U.S. for Vietnam on July 21 (46 years to the day). That was about all there was to the conversation with the gentlemen, and he left a short time later after eating his snack and quietly said “take care.” That was it.

It has been my experience that Vietnam veterans tend to be introverted about their military service and typically do not share their “war stories” very openly with others. You may share some stories with a veteran good friend that you’ve known for years because they understand, but it is rare that I see a Vietnam veteran openly sharing what he saw or felt while he was there. I never felt the urge to join the local Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW) chapter or the American Legion chapter, especially after directly coming back. Somehow it never felt right trying to relate to World War II or Korean War veterans.

I believe a lot of that has to do with the fact that we, as a group, were often shunned and despised for some reason largely out of our control. Maybe it was some of the atrocities that happened like the My Lai Massacre, or the incessant coverage on the nightly news that brought the war and the daily bad news into our living rooms every night, along with the casualty figures and anti-war demonstrations. Almost every family was touched, directly or indirectly, by the lingering war and everyone knew of a family member or friend that was either killed or wounded. Or maybe it was because we were the first generation of U.S. military to “lose a war.” I saw a T-shirt offered for sale on a veterans’ website that proclaimed, tongue-in-cheek, that “We were winning when I left Vietnam.”

On the same website another read “I want to thank everyone who met me at the airport when I returned from Vietnam,” accompanied by a single finger salute to the intended audience. Don’t get me wrong. I am glad for the renewed respect being shown for our veterans and those actively serving in the U.S. military, but there was a 30 to 40-year period where the attitudes gradually improved from disdain to tolerance to admiration. And it is about time.

I don’t think many of us expected a warm welcome when we returned. We all knew how divisive the war was, but I think we were all a little surprised by the open hostility that many of us encountered upon our return. Because every one of those Vietnam veterans sacrificed a part of their life for service to America, regardless of your political beliefs and no matter whether you agreed with the war or not. A lot of them made the ultimate sacrifice.

Running away from the country by going to Canada was a popular option at the time. Many tried to glorify it as a heroic act, but those that went into the military knew it was a cowardly option because we, too, were all scared we wouldn’t come back. At least guys like Mohammed Ali stayed and had the courage to openly fight to gain the status of Conscientious Objector. I didn’t like it and it nearly ruined his reputation as a profession athlete, but even I respected him willing to give it all up for his convictions. He probably could have ended up with an easy job like Elvis Presley as a military celebrity.

Most of us just did our job the best we could, and most of us will admit that we certainly could not be called heroes for anything we did, whether it was searching a village for Viet Cong or providing logistical services to the ones that did. And for every infantryman in harms way, there were eleven of us supporting them in one way or another. I actually cringe at the over-use these days of the word “hero.” Let me set this straight…I was never a hero in my life and cannot name one instance that qualifies me for the use of the term that deserves a pedestal. But there were plenty of people that met my definition. A hero, in my mind, is a person who may risk and sacrifice their own life for others, or an ideal, without personal gain. It is not simply doing a tough or dangerous job. This may be controversial, but I believe that a police officer, a fire fighter, farmer, or miner is not automatically a hero because they are in a dangerous occupation, but anyone can be elevated to that stature in dire circumstances where they will rise to the occasion. And a rock star certainly is not a hero. You can admire them, but they are not heroic.

How I Got into the Army

Prior to changes in the rules in December of 1969, there was truly very little that was fair about the draft process until near the very end of the war when all 19-year-old men were subject to the draft. In December of 1969, there was a lottery for all men born between the years of 1944 and 1950 in order to get everyone eligible for at least one year. After that first lottery, if you would turn 19 in that calendar year, you were eligible, no matter what your school or other family status was. There continued to be a number of deferrals made for special family conditions and obvious health issues.

In my case, the numbers were drawn for my year of eligibility on July 1, 1970, when my 19th birth date was drawn as #31. This meant that they would start drafting young men born on the date drawn, and keep doing so until the appetite for young men was satisfied. What was apparent to me was that, barring any physical condition identified, I would probably be in the U.S. Army no later than April of 1971. As the war was starting to wind down, history shows that the highest number drawn, and was actually called in for a physical, was 195, so the certainty of being drafted was very high for me. Try to put that in perspective, in the worst year, every other young man was being evaluated to be inducted.

Shortly after I got the bad news about my #31 status, I got married at the age of 19. We agreed that since we were starting our life together that we did not want the prospect of having our early married life interrupted by a stint in the army. What I did was a little unconventional in that I offered to place my name at the top of the list, by “volunteering for the draft.” I would always be considered a “draftee” and this status was not an “enlistment” where you were required to commit to a three or four year term of service, and the recruiters would promise you almost any field of training to get you to sign the papers. I can’t even begin to tell you the number of people that told me that they felt they were lied to in order to enlist.

I had been having some gastro-intestinal issues and I thought I may have an ulcer, so I figured that the physical would either reject me for some reason, or get me inducted. I wanted the finality of it all by either serving in the military or leaving me alone. On Friday morning, August 21, 1970, nearly two weeks after I was married I entered the Mart Building at 8:00 AM in downtown St. Louis where the army conducted their physicals. At 2:00 PM I was told that I passed my physical and was accepted as a new recruit and was sworn into the U.S. Army on the spot. The only thing I learned was that I needed a mild eyeglass prescription to correct my distant vision.

I called my wife and told her I would not be home, that I was shipping out that very evening for Fort Leonard Wood, MO and that I had about an hour that I could get with her if she could get down to the Mart Building soon. My father drove her down to say good-by, and after a few hugs and a lot of tears from my 16-year-old wife, I got on a bus headed to my first assignment for Basic Training. That moment became the beginning of my journey.

Basic Training

I thought basic training would be relatively easy. After all, I was in generally good physical shape, weighed 170 pounds and was 5’-11’’ tall. And I knew dozens, if not hundreds, of family, friends and school buddies who had gone into the service and managed to get through basic training. How hard could it be? But it was harder than I expected and I lost 15 pounds getting down to a lean 155 pounds and easily in the best shape of my life after those eight (8) weeks. Other guys gain weight probably putting on muscle, but they evaporated any fat that I had going in.

The Army had just loosened up on the mandatory buzz cut haircuts and facial hair for new recruits and many tried to get away with as much hair as technically allowed under the new guidelines. But not me. I used to cut my hair short in the summer when I was riding motorcycles and I was used to wearing a helmet all the time. Besides, while the long hair may have been popular with the hippie movement of the era, it antagonized many of the drill sergeants who didn’t like the relaxed rules and used any non-conformance as a reason to make life miserable for a recruit. I figured that it was going to be hard enough without inviting trouble, so a buzz cut just made good sense to me.

I remember one day I thought I would skip shaving because I thought my 19-year-old beard did not need daily attention. So as we were getting our morning inspection by the drill sergeants, I was singled out as one who didn’t have a fresh, close shave. I was told, that at the end of the day’s training, to come down to the drill sergeants’ office and bring a shaving razor with me. When I got there I was informed that I would have to dry shave (without any shaving cream) on my hands and knees and use the buffed floor as a mirror. Luckily, my beard was not very well formed and it ended up mainly being for show and not very painful, but I learned a valuable lesson about getting along in the military.

Along with all the standard fare of basic training, like physical training and calisthenics, running everywhere so we could “hurry up and wait,” hand to hand combat, first aid classes, learning to shoot, disassemble and clean the relatively new M-16 rifle, we were given aptitude tests to see what we might be good at once we were finished with Basic Training. This was the “Hail Mary” for all the draftees, as we all hoped that we had some skills that made us more useful as anything but an infantryman in Vietnam. But the realists in all of us knew that the Infantry training would likely be our next stop, or at least one of the other branches of the Combat Arms (such as Artillery or Armor, which means Tanks).

Prior to going into the Army, I worked as an engineering technician, or draftsman as they were called back then. I had taken every bit of available training while in high school and had found a job right out of school as a draftsman at a small automotive parts manufacturing facility. I was making $100.00 per week and while that wasn’t a lot of money, even at the time, my needs were simple and I was living the good life and living at home with my parents.

The Army’s aptitude tests recognized my engineering training and strong math skills and they told me that I was well suited for being assigned to the “combat engineers.” It sounded good at the time and kept my hopes up that I may be able to use some of my prior training to avoid the infantry.

Welcome to Artillery

What they didn’t tell me is that Artillery has a high dependence on mathematical aptitude, as opposed to being an “expert rifleman.” So when there were no apparent openings for combat engineers, I found myself being shipped to Fort Sill, OK to train for my Advanced Individual Training (AIT) in the Military Occupational Specialty of “13A10,” which is an artillery crew member. We graduated from Basic Training at Fort Leonard Wood and were on a bus that evening to the home of the artillery at Fort Sill, OK, which is just outside Lawton, OK.

In artillery AIT, we were trained to be crew members on all the artillery pieces in the U.S. Army arsenal. Other than the size of these weapons, the fundamental responsibilities of the crew members are all basically the same. These weapons included the 105mm, 155mm, and 8” Howitzers, along with the 175mm Gun. There were artillery pieces that could be towed behind a truck and others that were self-propelled, and resembled a tank. Howitzer design dictates a relatively short barrel, low velocity projectile, while the designation “gun” indicates a long barrel and high velocity projectile. Howitzers tend to be the most accurate artillery design and an 8” Howitzer projectile weighs approximately 200 pounds with a range of approximately 15 miles.

The 175mm Gun, on the other hand, has a projectile that is approximately 7” in diameter, weighs 150 pounds, with a range of approximately 20 miles. A full powder charge is approximately 7” in diameter and is 36’ tall, but it is also the least accurate weapon in the artillery arsenal.

One of the interesting things about the military is that you have time to train, train, train and do more training. It is almost mind-numbing at times, but the result is that everyone knows exactly what they have to do, almost instinctively, when the time comes. I thought there was no reason for that much duplication of training, but it becomes obvious when you are in a combat situation. Everyone, including the slackers, knows what their job is and anyone can fill in for the other crew members when it becomes necessary. This is a luxury the military can afford and has over the civilian world. In civilian life, you take a quick training course, either in person with an instructor or, more common today, on-line. You watch the PowerPoint presentation, take the token exam and then you are able to “check the box” to prove you took the training. The company notes in your personnel files that you are now trained. In a military environment, this training can literally become the difference between life and death in combat and that repetitive training nearly becomes instinct.

I must have shown some aptitude for the artillery as I was given two opportunities to advance by getting additional training. One opportunity was to go to Officers Candidate School (OCS) for one-year additional specialized training after AIT, at which time I would be awarded the rank of Second Lieutenant and become a commissioned officer in the U.S. Army. The down side was that I would have to change my term of service from two years as a draftee to a four (4) year enlistment. With the Vietnam War underway, I did not want to extend my time in the Army.

The second opportunity was to go to Artillery Combat Leadership (ACL) school at Fort Sill upon graduation of AIT. This school was established to train artillery crew chiefs to feed the specialized slots required in the ranks of artillery in Vietnam. A new class was started every two weeks and each class was limited to 30 students. The school consisted of 16 weeks of intense training into each and every artillery piece and learn the skills to be a gunner, assistant gunner or crew chief of each artillery piece. We also were given additional training in leadership skills, map reading, setting up an artillery battery, and escape and evasion.

The cool part of the ACL training was that you automatically got a pay grade increase from E-2 Private to E-4 Corporal upon start of the school, just four to five months after being inducted. And if you finished the 16 week course and graduated, you were awarded the rank of E-5 “Buck” Sergeant with an MOS of 13B40, which is an artillery crew chief. This means that in as little as eight (8) months after joining the Army, you could achieve the rank of sergeant.

But there was a down side to the ACL obligation. Upon completion of the course, you were then assigned for eight (8) weeks of on-the-job training within an active artillery crew that was headquartered at Fort Sill. These units were largely composed of Vietnam veterans who came back from their tour of duty, but had too much time left in their military obligation to be released back as civilians, or they were unable to be shipped overseas for some special reason. I found myself as a graduate of Artillery Combat Leadership school but was often called, in a derogatory manner, a “shake ‘n bake.” The Vietnam veterans generally disliked us because they were now reporting to someone who out-ranked them, was probably younger than they were, and less real world experience, especially in a combat zone. Here I was, a 20-year-old sergeant, with no real life leadership skills trying to lead a crew of Vietnam veterans in charge of a 155mm Howitzer that had little or no respect for me or the rank.

It took some time, but I was generally able to gain their respect and I think I learned a lot from them. You see, there are things that you can train for, but they usually cannot substitute for the ways things are actually done, especially in a war zone. It’s a simple case of street smarts versus book smarts. For instance, we were mainly trained in conventional warfare practices, which meant that the enemy was always supposed to be in one direction and the “good guys” were next to you or behind you. In conventional warfare, you always fired in one direction towards the battle front. While our training mentioned the differences in Vietnam, we were not given the specific training in the real world need to fire in any direction at a moment’s notice. What this means is that your firebase could very well be firing in 360 degrees since there was no “front.” You never knew which direction of your next fire mission.

Off to Vietnam

As I mentioned earlier, I left for Vietnam on July 21, 1971 after taking a leave between my ACL duty and my deployment overseas. Since you cross the International date line on your way to Vietnam, I actually arrived early in the evening of July 22 when we arrived at Bien Hoa Air Base, approximately 16 miles outside of Saigon, South Vietnam. I remember everything being almost surreal. As we stepped off the Boeing 707, operated by Flying Tigers Airlines as a chartered military transport, I felt the immediate blast of heat as we deplaned from the air conditioned airliner. It was approximately 7:00 PM (1900 hours in military speak) and it was a stifling heat well over 100 degrees.

For most of us, an air conditioned room was going to be a luxury over the next twelve months. I thought it strange that they told us to pack our heavy field jackets when leaving for Vietnam, but I found out why. Even the monsoon season in the winter was uncomfortable as it rained 28 out of 30 days of every month and, while it never got really cold temperature-wise, your clothes would never dry out and the dampness and chill in the air also made life miserable. But the weather in Vietnam wasn’t the only issue because when all things considered, we were really no worse off than previous generations fighting in wars in the heat of Southeast Asia or North Africa, or the cold of Korea or Europe, except we typically had a tour of duty that was defined and not “for the duration.” During World War II, my father spent three solid years in India as a communications specialist relaying code around the world (before the days of satellites) with no expectation of coming home until the war was over.

After we got off the plane, we were herded into a large assembly building, answered a roll call and were loaded on to buses for the 5-mile trip from Bien Hoa to the Long Binh processing facility. Strangely, the trip was one of the longest and most sobering experiences of my young life. I had been in the Army for nearly a year going through Basic Training, Advanced Individual Training (AIT), and Artillery Combat Leadership (ACL) School and I was now shipped overseas as a sergeant for an artillery crew. But none of that training ever really prepared me for the flood of sensory overload that I was experiencing that began with a convoy escorted by machinegun-armed Jeeps and gun trucks. I remember a sinking feeling deep inside that screamed at me “you are really here and this is for real.” No more boring drills, training exercises, or do-overs would be allowed. It was now all for keeps.

Trying to get some sleep that first night proved nearly impossible with the effects of jet-lag, the constant helicopter flyovers, loud music and talking and fire fights in the distance. There was a disproportionate number of blacks, Hispanics, college dropouts and poor white kids in the Army, as the Selective Service draft provided most of the recruits to meet the needs of the military.

National Guard and Army Reserve units at the time had a waiting list to get into their units, which effectively negated your possibility of overseas deployment, which can’t be said for today. And young men from privileged and influential families and good students would either join the National Guard, the Reserves or often get deferrals from the draft in order to attend school. None of that mattered anymore as I was starting my 12-month tour of duty exactly eleven months after being inducted.

After only a few days in Long Binh processing facility, I was shipped off to the 23rd Infantry Division Headquarters in Chu Lai. This was a little disconcerting as just before going overseas we had heard so much about the 23rd Infantry Division, also known as the Americal Division. It was also being called the “Americalley Division” due to the infamous trial in 1971 of Lieutenant William Calley and his platoon that were accused of war crimes for the massacre of 500 innocent Vietnamese citizens in the town of My Lai in 1968.

During our indoctrination to the Americal Division, we were required to spend at least one night on guard duty to defend the beach access to our compound. I remember watching the red tracers from fire fights across the bay with helicopter gunships attacking ground positions on the side of the mountains in the distant. Once again, the feeling that it was now all “for real” was reinforced.

After about four days in Chu Lai, we were shipped to the northern region of the Americal’s area of responsibility. My final destination was going to be just north of the DaNang Air Base, assigned to HHB, 3/82 Arty. This stands for Headquarters & Headquarters Battery, 3rd Battalion, 82nd Artillery Regiment, supporting 196th Light Infantry Brigade, and the 3/21 Infantry (3rd Battalion, 21st Infantry Regiment), which had a large local number of Infantry soldiers operating on the ground in the region. The 3/82 Arty was formed in 1916 and was known officially as the Red Dragons, although in Vietnam, our unit logo was a Mobil Gas type flying Pegasus horse, and our unit name was the “Flying Red Horsemen.” From a historical perspective, I’m not sure how all that changed over time.

Settling into my New Unit

After a few days of final in-country processing, I was surprised to hear that they did not need any artillery crew chiefs at that time, so two of us were going to be a part of a new unit assembled. This unit would eventually become part of the largest target acquisition group, at that time, in the entire U.S. Army. Our mission was to work in conjunction with U.S. Air Force security team members and we would be responsible for helping to defend the area near the DaNang Air Base located at the base of our mountain top.

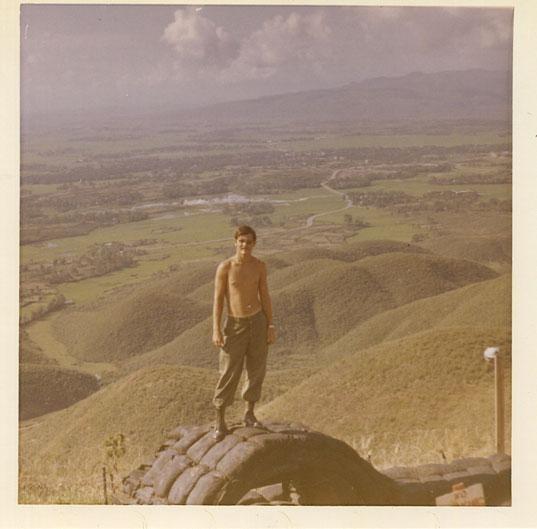

This mountain top was designated Hill 327, also known as “Freedom Hill.” The Hill 327 designation tells you that it is 327 meters (about 1,000 feet) above sea level and it was located in a mountain ridge (also known as “Division Ridge”) some 4 km (2.5 miles) southwest of the air base. The term “Freedom Hill” may have special memories to many Vietnam veterans that were stationed in the area. At the Base of the hill was a large Post Exchange (PX) where you all military personnel could get a haircut, buy prescription sunglasses, or shop for any little luxuries that were not standard military issued supplies. It was like a primitive Target store in that era.

Furthermore, the Freedom Hill complex had an amphitheater in back where they would host USO shows. I remember very clearly the day Bob Hope came with his troop of performers to entertain as many people as they could fit in. I was not one of the thousands who were able to get a ticket for the December 21, 1971 show held at the base of our hill, but we were able to listen to it on Armed Forces radio station AFVN.

But Freedom Hill was of strategic importance since the air base was so close and control of the hill would prevent the Viet Cong or North Vietnamese Army (NVA) regulars from lobbing rockets into the air base. The air base served as a home to many bombers that would go on bombing missions north of DaNang and into North Vietnam. We often watched them leave during the evening and return around sunrise.

Hill 327 had been defended by various U.S. Marine forces from April of 1965 until April of 1971, when the Americal Division took responsibility. On February 23, 1969, during the Tet Offensive, Hill 327 was the site of a significant battle between the Marines and the North Vietnamese Army. Marine casualties included 18 dead and 70 wounded, while the NVA suffered 75 killed or captured. The site of Hill 327 is still there if you look at Google Earth. It is a bare mountain top located at 16.03 N and 108.17 E coordinates.

Starting in April of 1971 defense of the hill was carried out by various platoons of the 3/21 Infantry, who were part of the 196th Light Infantry Brigade. The infantry soldiers were rotated out of the field for a week at a time for some relative rest, as the hill was mainly only a threat during night-time hours. By that time during the war, Hill 327 was a relatively safe place and easy duty for those of us serving at the time. Pulling guard duty around the Hill perimeter provided a relatively stress-free week compared to the normal missions of an infantry soldier.

Infantrymen reminded me of prehistoric animals compared to the rest of us and I admired their ability to accomplish the dirty jobs they were required to do under terrible conditions. Their clothes would literally be falling off of them when they returned from the “boonies” and they would draw more clothes (never new) for the next mission. I always felt a little guilty drawing the easy assignment that I got and I always appreciated those who earned their Combat Infantry Badge that they wore. In the final analysis, everybody who wasn’t infantry supported them in one way or another and they were the ones I most respected. From my perspective, they always endured more than their share of the suffering and hardship.

Our Mission

Together with another ACL sergeant that I graduated with, Gary Ritchie, we shared responsibility for three additional privates and were also functionally responsible for two Air Force security policemen that were attached to our group. Having the security police with us gave us direct access to the security team located on the air base. Our call name on the radio was “Skyhook” and we kept that name for the entire time I was on the hill.

As part of this new target acquisition team, we were taught to operate an observation post utilizing an Integrated Observation System (IOS). This was a 400 pound-device that looked like a huge surveyor instrument. It was mounted on a heavy duty tripod stand and consisted of three separate instruments that were all calibrated to coincide at the same location on the ground. These devices included a pair of 50x naval binoculars, a night vision “starlight scope,” and a laser distance range finder. Depending on the weather and terrain, targets could be identified at 30,000 km during the day and 4,000 km during the night.

Our primary responsibility was trying to identify suspicious troop movement in the valley to the southwest of our location and to identify the location of 122mm rocket attacks launched on the DaNang Air Base. Since we were part of the 3/82 Artillery, we had direct access to Fire Direction Control (FDC) that would coordinate artillery fire missions on suspected targets. Once we identified a target, we would simply take the reading of azimuth (direction) and distance to the target. With these two referenced points, FDC could calculate the coordinates of the target. Once clearances were obtained, the information was transmitted to one of our artillery batteries located in the region for a fire mission. The IOS device was credited with improving the chances of an artillery mission being successful at a rate of 70% on the first round, rather than the typical practice of using “bracketing” to walk the rounds into the intended target.

Also included in this Target Acquisition Team were a six-man team of anti-personnel ground radar operators commanded by a Chief Warrant Officer and access to anti-personnel sensors that were located in valley to detect movement.

From the beginning we realized we were incredibly lucky to draw the assignment. Early on we only worked nights so we would each take shifts of about four hours per night watching over the valley. We had a ¾ ton old Dodge “jeep” at our disposal and we had the freedom to use it to go back to our unit headquarters about five miles away every day. We had beds back in our hootches and a small electric refrigerator so we could keep cold drinks available.

Since we worked nights, and did our jobs quietly, almost no one bothered us and we had the opportunity to go into the Air Base for movies, steam baths and other PX privileges. In addition, we could go to China Beach, located on the South China Sea at DaNang and go swimming at one of the in-country R & R (rest and recuperation) sites. Life was about as good as it could get for technically being in a war zone.

During our time in Vietnam, we had the radio station run by Armed Forces Vietnam, or AFVN, to give us a little reminder of home. They played all the current and classic songs at the time. One of most vivid memories is that they would occasionally play a song performed live at the Woodstock Festival in 1969 by the group called Country Joe and the Fish. The song was called the “I Feel Like I’m Fixin’ to Die Rag” about Vietnam and the chorus went:

So it’s one, two, three, what are we fighting for

Don’t ask me, I don’t give a damn

Next stop is Vietnam,

And it’s five, six, seven, eight,

Open up them pearly gates,

Ain’t no time to wonder why,

Whoopee we’re all gonna die.

Upon completion of every verse, every military radio in the entire country would key their radio microphone so that the last sentence would be heard over the entire country. This was strictly frowned upon by the military brass, but no one was able to enforce the rule.

The same thing occurred when they played a song by the English group, The Animals. The verse was:

We gotta get out of this place,

If it’s the last thing I ever do.

Shortly after we got there, a 1st Lieutenant was assigned to be the leader of the Target Acquisition Platoon on the hill. He wasn’t much older than most of us, and he didn’t push too many rules on us and we got along good with him. We were told we had to move up on the Hill full time. We all thought this decision was fine with us as we thought there were too many rules that we had to endure living back at the headquarters. For instance, why in the world did we need to shave and have our polished boots every day?

Our hootches on the hill were similar and it meant eating C-rations instead of a hot meal back at headquarters, but it seemed like a good trade-off to avoid the silly rules “back in the rear.” There was a term we used for those guys in the rear. The initials were “REMF,” and was pronounced like it looks, which stood for “Rear Echelon M***** F******.

When we first moved to the Hill, there was a fairly large and reasonably stout wood frame structure that housed a meteorological group that provided weather statistics for military use. Several times a day they would launch weather balloons to gather data on temperature, humidity, atmospheric pressure, wind speed and direction at different altitudes, etc.

I experienced my first hurricane (or typhoon as it is called in that part of the world) on the Hill. It seemed especially ferocious to me and our hootches were no match for those winds. We were about 1,000 feet above sea level and three miles, as the crow flies, from the South China Sea coast. Our hootches were simple wood structures with 2 x 4 framing on 4 foot centers with a sheet of ½” plywood and corrugated metal roof. The wind would come in burst and it sounded like a freight train. We were huddled in our hootch when the roof caved in above us. Luckily no one was hurt, but since we had no decent shelter, we decided to try to get back to the rear headquarters and we made the scary trip down from on top of the Hill during the storm. When we eventually got back to the rear, it wasn’t much better. As the wind came in bursts, the structures around us literally exploded in front of our eyes. We took cover and waited out the remainder of the storm.

When it was over, I had never seen such devastation. Virtually no structure was untouched. And the damage was far worse than we would have experienced with modern building codes like we have in the U.S. Our hootches were designed for shelter, not enduring 100 MPH winds. We went back to the Hill as soon as we could to see how much damage we endured. Two of our hootches were completely destroyed, but the main building held up fairly well with little damage.

I remember looking at the devastation on the way back up to the Hill and expressed that I thought we should just leave the country, as the war was already winding down and there was so much work ahead to rebuild. I quickly came to the realization that leaving in a hurry was not going to happen and I was amazed at the resources that the logistics guys assembled to get things rebuilt and back to normal in a relatively short time. But my typhoon experience gave me an appreciation to this day of the damage that can be caused living within a path of a hurricane.

After the hurricane, the meteorological team decided to move to another location and we were fortunate to inherit their structure. It was like a small house with rooms sectioned off and a “living room” which became our main gathering spot for card games and general discussions, but no kitchen or bathroom. We had cases of C-rations available so we could eat anytime we felt like it.

One pleasant surprise was that at one point one of my best friends was able to come visit me 12,000 miles from home. Larry had enlisted into the U.S. Air Force upon graduation from high school in 1969. He was eventually shipped to Vietnam several months before me as a loadmaster, who loaded planes with bombs at the Cam Ranh Bay Air Base along the east coast in the lower third of the country. On his way to going on R & R to meet his wife in Hawaii, he flew into DaNang to catch and had a short layover while awaiting his flight to Hawaii. Since we had a landline, he was able to call me up on the phone and I took the jeep off the Hill to meet him at the terminal and I took him up to our Hill so he could meet my crew, play some cards and just catch up. It was something that I could never have envisioned would happen that far away from home.

Life was obviously relatively good for being in a war zone. We were never in any serious danger in our current location and our job was simple. Just stay awake during your shift at night and keep an eye open for any unusual movements and activity at night. The primary threat that we were on the lookout for was 122mm rocket launches directed toward the air base. The rockets had a firing tube and resembled a large mortar. They could do a lot of damage if they hit a critical target, but they were notoriously inaccurate. Still, being anywhere near a hit on the ground could cause a lot of damage. In 1968, a large number of rockets hit the air base and caused a large loss of life and considerable damage, but the frequency of launches at that time were infrequent. They launched them just often enough to let us know they were still out there and that we couldn’t let our guard down.

When rockets were launched they would leave a “rooster-tail” of flames as they ascended into the sky. They looked like huge bottle rockets going up into the sky. It was our job to watch a huge area (approximately 180 degrees) at all times to spot a launch, or follow the trajectory back to where we suspected its launch, get the IOS device trained on the location of the launch site and call in the data in order to request a fire mission of artillery.

Troop Strength Reductions

U.S. troop strength peaked at 536,100 in 1968 with nearly 17,000 casualties. In 1971, when I went to Vietnam, U.S. troop strength had already been reduced to 334,600 as the South Vietnamese Army increased their forces to 1,100,000 members and the U.S. strategy under President Richard Nixon and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger was to transfer more and more of the country’s defense to the South Vietnamese. An intense training effort was under way to get their forces trained to handle their own defense, so that the U.S. could withdraw from the quagmire that started for us in 1966 after the French gave up the fight. At one time, we had to ARVN soldiers attached to our unit on the lookout post and they coordinated with the South Vietnamese military.

At the beginning of 1972, U.S. troop strength was down to 156,800 and in January of 1972, President Nixon pledged to withdraw even more troops in order to meet a goal of 100,000 by April 30, 1972. This was especially important to me since fairly simple logic allowed me to calculate that, if Nixon honored his pledge, I would be back to the United States by the end of April, thereby cutting my tour of duty to a maximum of nine and one-half months, instead of the required twelve.

Off to the Firebase

Time was passing at a reasonable rate for me on Hill 327. I knew I was lucky and I thanked my lucky star. I was determined to sleep every free minute that I had so time would fly by faster. After you were in-country for six months, you could request an out-of-country, 7-day R&R that did not count against your 28-day vacation allowance. The Army would fly you free to Hawaii, Bangkok, or a few other destinations for a seven-day vacation. They also had a program called a “7 and 7” in which you took a total of 14 days off, with 7 days free and charging you an additional 7 days against your vacation allowance. Many soldiers met their wives or girlfriends in Hawaii and some would fly back to the states to be back home.

At my six-month point, I requested a 7 and 7 and had planned to fly free to Hawaii and pay my own way to and from St. Louis to visit my wife and son. Since these leaves were granted by seniority of time in-country, they turned down my request for leave. Shortly thereafter is when Nixon pledged to reduce the troop strength. At that point, it was obvious to me that I’d be home within three and one-half months, so I decided with my easy assignment, I’d just wait it out.

The Army was now in a rush to start reducing the troop strength by more than 50,000 in about 100 days. We had a landline telephone on Hill 327 for military communications only. I got a strange call from the brass located back in the rear that made me the following, very unusual offer:

I could leave Vietnam immediately (in the middle of January after only 6 months there) if I would agree to finish my tour of duty in South Korea, but there was a caveat that I would have to go to Korea for 7 months, because Korean tours were 13 months instead of 12 in Vietnam.

I didn’t have to think about it long. The pros were that I could leave Vietnam immediately, but the cons included a certain 7 more months versus a likely three and one-half, I already had an easy assignment, and one of the biggest cons was that Korea is miserable in the winter. I told them “no thank you” and that I’d prefer to stay where I was. Gary Ritchie made the same decision and within days we were both transferred from our current easy assignments to separate artillery firebases to take an assignment that we were trained for.

I ended up on a small firebase to the southwest of Hill 327, which was known as Hill 260, and was called it FSB (Fire Support Base) or LZ (Landing Zone). The remaining site of Hill 327 is still there if you look at Google Earth. It is a bare mountain top located at 16.03 N and 108.17 E coordinates.

My new unit was B battery, 3rd Battalion, 82nd Artillery Regiment. It was one of the batteries of six M-102 (105mm) Howitzers, which were the ones designed recently for easily shooting in 360 degrees. They had a pivot point under the main instruments and barrel breach and although they weighed 3,200 pounds they were so well balanced that one person could pick it up by the tow bar and point it in any direction required for the next fire mission.

My MOS of 13B40 qualified me for one of the following functions. I could be the gunner (who controlled the sight and direction we were pointing the gun), the assistant gunner (who controlled the angle that we would be shooting into the air), or I could be the Crew Chief, which required the rank of E-6 (staff sergeant) or E-5 (buck sergeant).

The crew I was assigned to already had an E-6 Crew Chief, so I took over the position as gunner. Almost immediately after joining the crew, we were assigned to be the duty gun. Every day a different crew took their turn to be the duty gun for the night. It usually meant you would not get much sleep that night, unless you were really lucky. While the entire battery would be awakened in the event of a full-fledged fire mission, the duty gun would handle the mundane chores like shoot illumination rounds as requested by various units. One of the other duties was to test-fire “delta tangos,” or defensive targets for all the units in the area and reciprocal targets for other fire bases within our range. This meant that the requestor would determine where they felt they were most vulnerable from an attack and we would get those coordinates and test fire artillery shells at those locations, so that the information was stored, approved and ready for firing on a moment’s notice. If we received a call for a certain delta tango, we could literally get an artillery round to the target within two minutes of the request.

Almost right after I joined the crew at my new unit, our gun was the duty gun for the night. We were shooting delta tangos for the various units, when all of a sudden, the Officer of the Night yelled to “cease fire” and every one was ordered to step away from the gun without touching it. I knew this was a bad, bad omen. This meant there was some sort of serious error and there would be an investigation. We were not told what the exact problem was; only that a round landed too close to our own forces. We were not immediately told if anyone was injured or that it was just a close call.

When one of your own forces inflicts injuries on your people, this is what is known as “friendly fire.” My heart sunk with the possibility that I may have been responsible for injuring one of own guys. There are only five, logical possibilities of fault when this happens. They are as follows:

1. The gunner (my job) fired the wrong deflection (direction). This is much easier to do than you would expect because each gun has three sets of aiming sticks and there are 18 sets of these aiming stick lights on a fire base. Keeping track of them, especially at night, is no easy chore because the firebase is so small.

2. The assistant gunner fired the wrong elevation (angle), which is possible, but less complicated.

3. The crew fired the round artillery shell, which could be type of round, powder charge (there are seven), wrong fuse, or proper time set on a timed fuse.

4. Wrong fire mission data, which is nearly impossible because the data is calculated manually, and confirmed by two independent computer runs at different locations. All data must agree before a round can be fired.

5. The wrong coordinates were supplied by the requestor or forward observer, and they essentially called a fire mission on themselves. While this might sound incredulous, remember that there was no such thing as GPS and in order to determine where you were, you had to triangulate your location from other landmarks, often in very dense locations.

An officer came out and verified that all the mission data on the gun was correct and eliminated the first four causes within 30 minutes while we nervously awaited the results. This left the fifth cause the apparent issue and it was found that someone had incorrectly identified their location and ended up calling in artillery on themselves.

It was not until the next day that we found out that several U.S. Army infantrymen had not been killed, but had been injured, although we were never given the exact nature of the injuries. This was more common than many people realize. In Vietnam, 9,107 people died of “accidental causes” which is approximately 15% of the total casualties.

In 1979, a made-for-television movie was released that starred Carol Burnett and Ned Beatty and documented a real life story about a family’s attempt to find out how their son was actually killed in 1970. This movie was eerie to me because the cause of death turned out to be “friendly fire” from an artillery unit. What she never could accept at the end was that in a combat situation this kind of thing happens far more than one would expect and the reality is that with the danger involved it is almost certain to happen eventually, no matter how hard you try to prevent it.

Shortly after the friendly fire incident another extraordinary thing happened. Every day after lunch, they would usually allow everyone to take a short nap as our hours that we were theoretically on call were 24/7, so we grabbed some sleep any time we could. During one of these brief naps, we heard the sound of an M-16 rifle shot. When we investigated it we found that our crew chief went into his hootch and committed suicide. Of the official total death toll listed as 58,220 during the Vietnam War, he ended up being one of only 382 were ruled as suicides.

I had been so new to the unit that I was unaware of any problems that this chief was having. I don’t know if the friendly fire incident was partially at cause, or he just had other issues that weighed heavily on him, but I then inherited a shocked crew and we carried on the best we could.

I have to point out that the guys in an artillery crew were a rowdy bunch and not the most disciplined members in the Army or in society. In fact, the best you could ordinarily say is that they were OK guys just trying to do their time and get home. They were always looking for ways to get out of work or do things “half-assed” and never give their all, EXCEPT one case. While you constantly had to stay on top of them, you NEVER, EVER had to ask them to give it their all when a fire mission was called. Somehow, they all agreed on one thing. That is, if our infantry guys needed our help, they got every ounce of attention to get the fire mission out and done right. This was always amazing to me to see the difference in attitude when something serious was going down and I was incredibly proud of them when it came to doing their job that they were trained for.

My Move to Hill 350

I was only on Hill 260 for about a month when we were told that we were going to rotate to a different firebase on a far ridge to the west of our current position. The new assignment would be on Hill 350, otherwise known as FSB or LZ Maude. This was an old and established firebase in a remote region on top of a hill with the only access by helicopter. Half of the hill was devoted to artillery operations while the other half was an infantry base.

It was at that time that they had an opening for a computer operator in Fire Direction Center (FDC). Remember that this was early in 1972 and most people don’t realize that the military was one of the originators that were driving the development of computers for warfare. Before the days of computers, fire missions were calculated using artillery calibrated slide rules (if anyone under the age of 50 knows what they are) to calculate distance, powder charge, angle of barrel and corrections based on wind speeds at various atmospheric strata. It was something that took a took a considerable understanding of math and specialized training, but FDC was also using a portable computer powered by a 120V generator.

This computer was known as the FADAC (Field Artillery Digital Automatic Computer) and was first used in 1960, being the first semi-conductor based general purpose digital computer. This was no laptop toy for playing games! It was serious hunk of technology that was approximately 10” wide, 24” tall and 30” deep and weighed nearly 200 pounds. It consisted of 1,600 transistors, 9,000 diodes, 6,000 resistors and 500 capacitors. There is only one known surviving example of these computers in the Artillery Museum at Fort Sill, OK since they were considered hazardous waste when they were de-commissioned, due to radium used in their dials.

Operation of the computer was relatively simple and only required punching in the coordinates of the target on the keyboard. Since the computer had information stored where it was located and topographical local information, it could calculate all the necessary information required for a fire mission. The data provided included the deflection (angle to the target), elevation (angle of the barrel), powder charge required to shoot the round to its target and time of flight, which would allow a timed fuse to be included for an air burst. All of this data was then corrected for temperature, barometric pressure, wind speed and direction at various levels of the atmosphere. Meteorological data was fed into the computer every twelve hours to stay as current as possible.

The Fire Direction Center had a Lieutenant responsible for the group located on the hill with the artillery battery. We worked in a sea container type office where the FADAC, radios, charts and personnel could be housed. An E-5 Spec5 was in charge of each of two shifts. Other than the hours, the job was easy, safe and I was on the cutting edge of computers and I didn’t even realize the role they would have in the future. The guys with slide rules could never beat the computer spitting out information, but the FADAC was very slow by today’s standards, and the slide rule guys were always within 30 seconds of an answer on all the calculations.

This is how it worked. A fire mission was called in with coordinates of the target. The slide rule guys would run their calculations manually, while I would plug the information into the computer. Once both results were attained, we would check to make sure that all data was within a tolerance of a few mils, not degrees.

Here’s a little known fact. In artillery calculations, we divided a circle into 6,400 mils instead of 360 degrees. This gave us the additional granularity required for the accuracy needed. So 1,600 mils was the same as 90 degrees in a conventional quadrant. It eliminated the need to have

calculations in degrees, minutes and seconds.

If the data was within tolerance, we would use the computer generated data and would use the radio to run the data past an FDC specialist located back at battalion headquarters. If the two computer generated data sets agreed, and they should, then we would be given authorization to shoot the mission as long as our Intelligence group also provided approval. This was an important step because our Intel guys were supposedly up to date with our troop movements and location of friendly forces, like the ARVN troops and friendly villages.

We worked 12 hours on and 12 hours off. Everyday. There were no holidays on the hill. But out on the firebase, we were pretty casual. You weren’t required to shave daily, your boots could look terrible, you could wear cut-off shorts and go shirtless and discipline was minimal.

While discipline was relatively lax, everybody pulled a guard duty shift at night. Each person would spend two hours a night in a bunker, which was a sandbag covered culvert half overlooking the firebase perimeter. We were lucky, in the sense that since it was an old firebase, it had been well developed, including perimeter flood lights run by a generator and all the vegetation had been burned off. On a regular basis, we had Chinook helicopters drop 55 gallon drums full of diesel fuel around the perimeter. When the drums hit the ground, they would burst and spill fuel all over the side of the hill. It was then that someone would throw an incendiary grenade into the fuel spill and giant fireball would erupt, thereby burning off any vegetation around the perimeter. That’s why you won’t see any green vegetation near the top of the hill.

Occasionally some troops would be allowed to go back to the rear by hitching a ride on the daily helicopters bringing food or supplies. Believe it or not, it was hard to get people to volunteer to go back to the rear, with the requirement to shave, get your uniform looking good and dealing with all the REMF’s back in the rear. But the worst part was that if you decided to go, you were covered with requests from all your buddies to pick up something special for them “while you happen to be there,” since they didn’t want to endure the requirements of the trip. If you went back, you essentially ended up being a shopping service for everyone on the firebase.

Overall, my duty assignment on Hill 350 was without any major incident and the time went by fairly quickly. You were either working or sleeping. The one problem I encountered was in late March, 1972 and we had just inherited a new 1st Lieutenant that was new in-country and would be in charge or our FDC. As the U.S. troop strength was being reduced, they ordered our unit to be air lifted by military transport planes from DaNang Airbase up to the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) on the border between North and South Vietnam during the first week of April. This was being done to allow the withdrawal of the 101st Airborne Division.

I had received orders about April 1 that I would soon be released from my assignment in Vietnam and be allowed to begin the process of leaving the country. This meant that I was one of the troops over the 100,000 limit that were headed out of the country. With my current unit getting ready for re-assignment up north, our new lieutenant threatened to prevent me from getting my release as he said my position was mission critical to the move. It was one of the only times I was disrespectful to authority when I told him that he was new, had a long time to go, that I had done my turn and if he prevented me from going home, he would regret it. I never knew whether he was serious or not, but I certainly was when I told him. He backed off and did not stand in the way of me leaving. I actually believe he was just trying to give me a hard time, but I did not find it funny.

My newest orders meant that I had served a little over eight months in Vietnam and my remaining time (about 10 to 14 days) would be spent out-processing in Vietnam, flying back to the United States and out-processing out of the Army once I got back. During my out-processing reviews back in the rear, one of the officers told me that I was supposed to have received a Bronze Star citation and if I was willing to spend three more days in Vietnam, they could have this expedited and corrected. I honestly knew that I had done nothing to warrant such a commendation and that I just wanted to get home, so I told them not to bother. The officer told me that he would turn in the paperwork anyway and have it sent to me after I separated from the Army. I never received the Bronze Star, nor do I feel that I did anything special to earn it, so I never pursued the matter. People far more deserving were in abundance.

It was common knowledge that if you returned from an overseas assignment with less than six months left, they would generally release you back to civilian life as it was too much trouble and costly to send you to a state-side assignment for the remaining time and I was looking to only a few more days as a soldier.

Leaving Vietnam

I was surprised when I got to the out-country processing center that was located in DaNang that I met up with a number of my ACL graduating class that I had lost track of. We spent a couple days together, shared stories and experiences and flew back on the same 707 from DaNang. I remember boarding the chartered airliner run by Flying Tiger Airlines at the DaNang Air Base, and from the window of the aircraft I could see M-102 Howitzers being loaded on to military transport planes for the trip up north. It was almost surreal knowing that I came very close to being one of those headed up north with them.

The inside of our 707 was eerily silent as everybody was thinking about all the bad things that could go wrong this close to leaving the country. As the airplane taxied to the end of the runway and the pilot provided full thrust, there was complete silence as we were speeding down the runway, until the very moment that you could feel the plane lift-off the runway. At that exact moment I heard the loudest cheer of jubilation from more than 200 veterans on their way back to “the world.” It was chaos inside with congratulations all around, and we all knew it was finally over for us.

We flew into the Oakland Army processing facility where you spent five agonizing days going through the slow process of separating from the Army. We all had physicals, hearing and vision tests, meetings with psychologists and all sorts of official paperwork reviews, but mostly we went crazy with the hurry up and wait of the lines while they were overwhelmed with the large number of troops returning in such a short period. We finally received a new Class A uniform, were paid in cash for the amount that they owed us for our service and given an airplane ticket to make our final trip home. We were all transported to the San Francisco airport so that we could catch flights to various destinations throughout the country to our homes.

On April 13, 1972, three days before my 21st birthday, I said goodbye to one of my closest friends, Gary Ritchie, whom I spent most of my time with, in front of the San Francisco Airport. He was on his way back to Chicago and I was headed back to St. Louis. As a bonus and surprise, the airline upgraded me to an empty first class seat on my trip home.

Settling Back into Civilian Life

I was greeted at the St. Louis airport by my wife and young son, and the rest of my family. I don’t remember much about the first few days back home, but I think I returned back to the job I left as a draftsman about two weeks later.

I was anxious to get my life back on track, but while many veterans made plans to go to college full time on the GI Bill, I was trying to raise a young family and didn’t think I could afford going to school full-time. While I was in Vietnam I had correspondence with my employer about a possible sales related position when I returned, because I saw in that company that we designed and manufactured products that the sales force thought filled a need in the market. The sales group basically determined the direction of the company’s focus. It now seems silly that I was a 20-year-old kid with one-year of experience making these requests from around the world.

After six months back on the job with no movement on finding an opening in the sales group, I left the company to become a 21-year-old state licensed “special agent” selling life insurance for the Prudential Insurance Company in the St. Louis area. I tried to focus on returning veterans who lost their life insurance upon separation from the military and I tried to get them to replace it with new whole life insurance. I thought I would be able to relate to them, but either they had no money or I didn’t have the personality or skills to sell to the general public. I found that you have to have a certain gene in your body that ignores the rejection that you get by constantly being told “no thanks.” This position lasted about four months before it became apparent that I was not a born salesman and I had to take another look at my future.

I quit my job at Prudential one day and started looking for another position the next. There were a lot of returning veterans out in the job market, but I had two good leads and interviews. I made the decision that I would take the first job offered and shortly afterwards I went to work as a draftsman for a large, prestigious, regional construction company that was celebrating their 100-year anniversary located in downtown St. Louis. My starting salary was $160 per week plus overtime. While I didn’t have any formal training in construction, I did get access to a fabulous mentor who took me under his wing and taught me as fast as I could learn.

After a year out of the service I attended night school at the junior college taking 6 credit hours per semester for about seven years, but I felt like I was burning a candle at both ends and never graduated from college.

This was the start of a 44-year career in the engineering and construction business that I have eventually retired from. My employment included the following companies:

Fru-Con Construction (St. Louis & Houston – 15 years)

Korte Construction (St. Louis – 4 years)

Parsons Corp. (Houston – 4 years)

Fluor (Houston – 15 years)

Jacobs Field Services (Houston – 6 years)

My Years of Activism

Once I was back in the U.S. I became more and more disenchanted with our country’s continued involvement in Vietnam and there was a short period when I let my hair grow and didn’t shave and grew a beard. I remember my mentor kidding me and offering to pay for my haircut, but I let my hair grow longer as I was determined that I would never have someone make me get a haircut again.

I found myself drawn to others who were of the same mindset. I was able to contact the local chapter of the Vietnam Veterans Against the War (VVAW). I felt a camaraderie with these guys and what they stood for. My father never understood my commitment to this group, but I tried to explain that their demonstrations were different because they had a perspective that was real and authentic because of their personal relationship with the war. People who were not there would not understand the frustration of fighting an enemy that appeared friendly in daylight hours, but supported the Viet Cong at night. The war was not “winnable” by conventional standards.

I remember writing home about my observations about the hopelessness of winning this war. There were several occasions when we spotted rocket attacks on the air base and we were told that we could not get an artillery fire mission approved because the target location coordinates were in a “friendly village.” I remember remarking one time “Friendly village, my ass.” In each case the U.S. Air Force would send out the security police the next day to investigate and find evidence of a rocket launching. It was just so frustrating that we couldn’t do anything about it.

I attended two major demonstrations in the short time I was associated with the group. One is where they threw pints of their own blood at the entrance to the U.S. Department of Defense Mapping Headquarters in St. Louis. It was peaceful, but messy.

The other was a demonstration in the support of the trial of the “Gainesville 8” members of the VVAW. This group of veterans was accused of conspiracy to disrupt the 1972 Republican National Convention, but they were exonerated in less than four hours by the jury when it was exposed during the trial that an FBI agent had infiltrated the organization and had actually helped lead the plans to disrupt the convention. During the trial, our local VVAW chapter set up a vigil that amounted to a guard-post with sandbags, toy M-16 weapons and full Vietnam jungle fatigues to “protect the Blind Justice” statue on the steps of the U.S. Courthouse in downtown St. Louis. I was even photographed during the demonstration and the photo appeared on page 3 of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch newspaper with my name identified.

The Vietnam Veterans Against the War were a very vocal group at the time and if you don’t think the government was paranoid about these groups, think again. I was visited at my home by two identified members of the Federal Bureau of Investigation. They asked to talk to me and showed me dozens of photographs of “subversives” and asked me for help in identifying them and their location. For the record, I did not recognize a single photograph. And later, our rental house was broken into and nothing of any significant value was stolen. The local police were called, but never able to solve the case. Maybe I was paranoid, too, because I thought the FBI may have been to blame.

Three years from the date that Nixon promised U.S. troop strength down to 100,000 on April 30, 1972, the South Vietnam government officially surrendered to the North Vietnamese and this chapter of history came to a close on April 30, 1075, along with my anti-war involvement.

The Final Chapter

Although I left Vietnam early in April of 1972, my artillery unit stayed without me, but not for long. They ended up going back to Hill 260 and on August 10, 1972 they fired the last artillery round of the U.S. involvement in the war. The unit was B Battery, 3rd Battalion, 82nd Artillery Regiment and it was a ceremonial white phosphorus round fired from Hill 260, where I became a crew chief for real.

The 3/82 Arty was part of the 196th Light Infantry Brigade. The 196th proudly states that they were the first full Army unit to be sent to Vietnam on July 15, 1966 and the last unit to leave on June 29, 1972. During that period the 196th suffered 1,188 killed in action with an additional 5,591 wounded. The 196th Light Infantry Brigade is still in existence and now has its home base in Hawaii with units also serving in Guam.

The results of the Vietnam War were not very good from the perspective of the total outcome, but I have never believed that it was because of some flaw of the young men and women who served there. Our outcome was the result of trying to find a way to fight an unconventional war with our hands tied by political leaders who didn’t have the resolve to do what was necessary. Maybe you can never win in these circumstances. I’ll let others ponder that question.

I’m not sure we have learned all that much when you look at the quagmire of our involvement in Afghanistan. While we may have spent a lot more time and money in Afghanistan, we never reached the level of troops on the ground or large number of casualties of the Vietnam War years. We still can’t figure out how to get out.

Times have changed. Active members of the military and veterans are finally receiving appreciation from all walks of life and those who have chosen to serve their country can be proud of their sacrifices they have made.

In June of this year, over 45 years after leaving the Army, I purchased and now own a “Vietnam Veteran” baseball cap that I occasionally have the urge to wear. I wore it yesterday and a stranger came up to me, shook my hand, and said “thank you for your service.” It took a long time to hear those words and I realized that all I ever wanted was to have it acknowledged that we did our best under very difficult circumstances. It’s now time to move on with my life and try to enjoy retirement.