Author's Name: Jay Harden

Title: "How I Survived the Bulge and Other Stories: An Oral Interview with Uncle Sam"

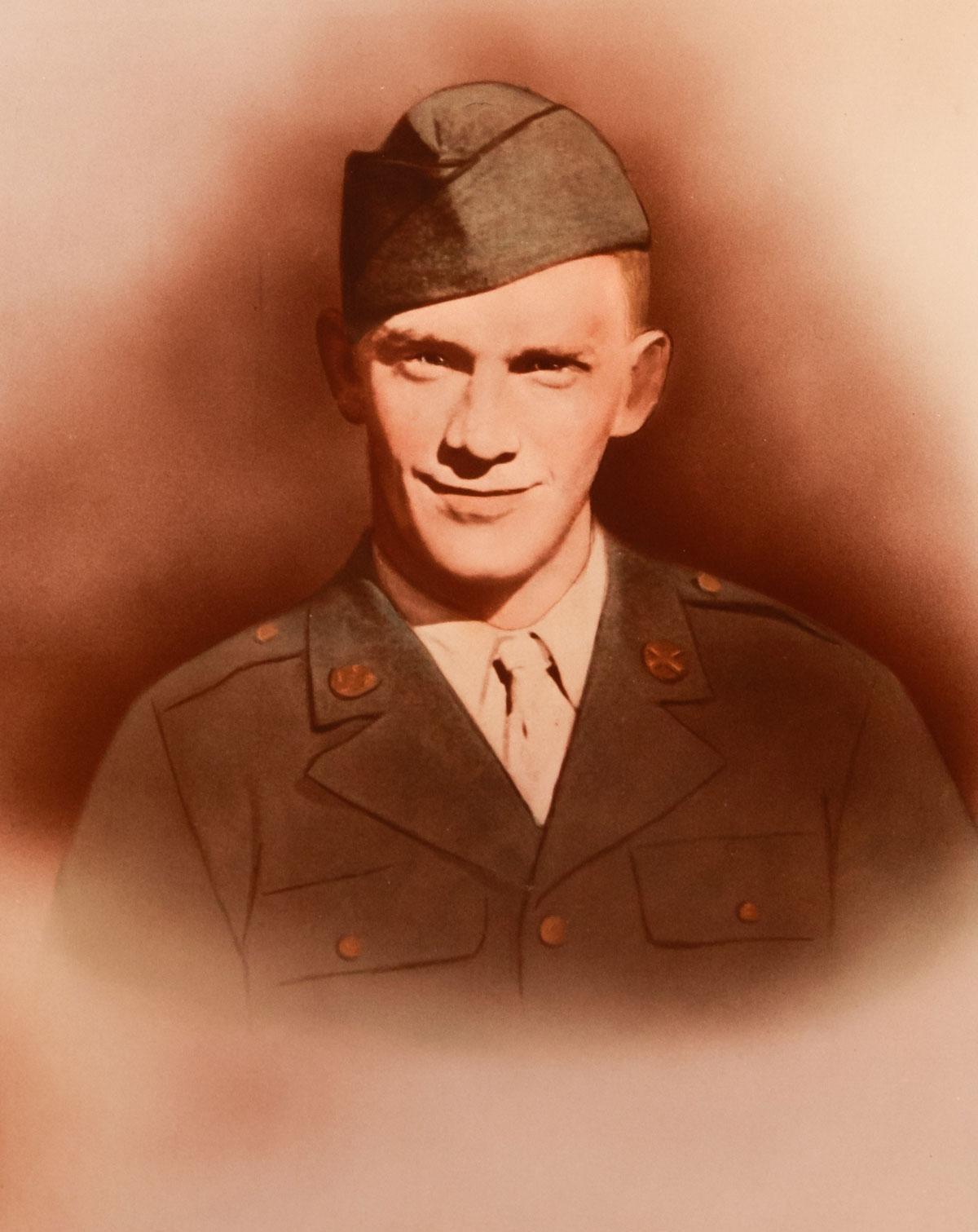

All veterans have a close relation named Uncle Sam; we work for him and what he represents. A Vietnam vet friend of mine also has an admired uncle, a real Uncle Sam. Samuel E. Losh, Jr. is 93 and a veteran of World War II. He recently visited Washington, DC with his grandson, courtesy of Honor Flight. Honor Flight is a non-profit organization that transports veterans, at no personal cost, to see their war memorials in Washington. That experience breathed fresh vigor in Sam and ignited his memories, now all the more important to record since the Military Personnel Records Center fire of July 1973 in St. Louis destroyed his service records.After his trip, Sam finally decided to preserve his own Army stories for family and friends in an oral interview with the author on October 16, 2017. These are Sam’s memories that he wanted to record with me.

Sam remains bright-eyed and bushy-tailed with a persisting sparkle for life. In particular, Sam remembers why he didn’t die in the Battle of the Bulge.

Sam worked as a welder’s helper making bomb racks for the military and could have gotten a deferment, but his brother and buddies had already enlisted and he came from an extended St. Louis family of several Navy men. Sam tried to join as a sailor, but was disqualified for color blindness. His stepfather and brother were in the Army, so Sam went to Jefferson Barracks and volunteered at age 19 to wear green instead of blue. That was in December of 1942.

Sam ended up on a train bound for Camp Callan, California, 15 miles north of San Diego, and 13 weeks of basic training in anti-aircraft artillery.

Sam qualified as a small arms expert on the World War I Springfield 1903 .30-06 bolt-action rifle with grenade launcher attached and ended up assigned to the .50 caliber machine gun that supported and defended the cannon crew. He also trained in the Mojave Desert on the old 37mm auto cannon left over from WWI that jammed a lot. Sam’s job was to lie under the cannon and catch the very hot unfired rounds and pass then to another man to put in a misfire pit. Lucky for Sam they started training on the 40mm Bofors anti-aircraft automatic cannon intended to protect the nearby field artillery from air attacks.

He graduated from basic training on January 9, 1943 as a member of the 462nd Anti-Aircraft Artillery Automatic Weapons Battalion (462nd AAA AW Battalion) and started his journey to the European Theater of Operations (ETO).

After graduation, Sam was sent to Camp Haan in Riverside, California as a replacement gunner in a new unit just starting their basic training. He was told he had to repeat all of basic training, but Sam angrily refused and was disciplined with a new occupation in Kitchen Police (KP).

In our conversation, I asked him how he kept his sense of humor during war. “I don’t know. I was just a kid and everything was funny to me. Even the obstacle courses were fun.”

Sam, to this day, still has that positive perspective of an immortal 19-year-old. He mysteriously told me early in the interview, “If I had it to do over again, I’d prefer KP.” “Why?” I asked. “Well, as I will tell you, KP kinda saved my life.”

In April, Sam headed for the U.S. Army Amphibious Training Center at Camp Gordon Johnston in Carrabelle, Florida where he learned to jump from a burning ship hanging from a cargo net on the side while the landing boat bobbed with the waves up and down and away from him. He also learned to swim through and under flaming oil on water.

In May, they pitched pup tents in the mud of Gallatin, Tennessee for simulated war games with the 79th Infantry Division. The maneuvers seemed like a furlough to Sam and the hardened men of Battery A.

In June, they were trucked to Camp Stewart, Georgia for more weapons practice and training in invasion disembarkation from a Higgins Boat. Once Sam jumped from the boat and sunk in a big hole while the following guys jumped into the water on top of him. Sam nearly drowned and had to abandon his gear so he could finally surface. The officer above asked, “Where is your rifle and pack?” Sam had to dive down again and retrieve it all.

During July, that battalion went to Camp Pickett, Virginia and the luxury of barracks, bed, and showers as the truck drivers practiced black-out moves. They also spent a week on the Atlantic coast at Camp Bradford, Virginia learning to use the landing craft that later cracked the beaches of Normandy.

While home on a three-day pass, Sam called his 17-year old girlfriend, Laura, and said, “Pick out your best dress and meet me in the morning. We are getting married.” Laura’s stepfather was in politics and got the three-day waiting period waived. Sam and Laura drove around until they found a Lutheran minister working in his church garden and he agreed to marry them. Laura’s mother and Sam’s sister and brother-in-law were witnesses. At the end of the pass, Sam reported for duty. They did not see each other again for almost two years. Laura is still the loyal love of his life after 74 years of marriage.

His point of overseas departure in the states was Camp Myles Standish south of Boston, Massachusetts. There the 462nd joined up with the 17th Field Artillery Brigade. Sam learned the art of freezing in his summer fatigues, a ruse to mislead spies into thinking they were headed for the Pacific. There, while peeling potatoes during KP, Sam met an old mess sergeant who gave him his life-saving advice. He also mastered the art of “hurry up and wait” and confessed that he stole officer steaks on occasion for private consumption.

After 11 months in the U.S., Sam left Boston for the ETO on November 6, 1943 in a converted freighter, skipping wave over wave across the Atlantic and practicing personal combat with another unseen enemy, seasickness. Sam stayed well most of the trip until 3 days before port in Great Britain where they finally received warmer clothing.

When allowed, the G.I.s visited the local pub in Pembroke, Wales to relax and drink ale. The girls in this poor lumber town naturally sought out G.I. money for free drinks. (Like the other privates, Sam’s base pay was $50 a month; he kept $5 and divided the remainder between Laura and his mother.) G.I. generosity did not sit well with the local testosterone of miners and lumberjacks. “We got beat up regular,” Sam said. So one morning at 2 A.M., the Captain came to the barracks and ordered, “Fatigues, boots, helmet liners, let’s go.” He led his men to administer some physical attitude adjustment to those young men. From then on, Sam recalled, they had no trouble spending money in town.

The 462nd arrived on the east coast of England just before D-Day, ready for battle.

Seven days later, June 13, 1944, Sam and Battery A landed at Omaha Beach, Normandy, in an LCT (Landing Craft, Tank) with his .50 caliber machine gun, their truck, and 40mm cannon in tow. Their first sight in Europe was Allied bodies stacked on the beach beside unexploded mines and other debris of war. That memory still brings tears to Sam’s eyes.

Sam recalled, “I had some crazy experiences there. Thank the good Lord I made it.”

For example, Sam said, “My first combat was with a spider. When I landed in France I started to go deaf. Then the medic found a dead spider in my ear.”

Sam and Battery A lived in the field, constantly on the move. “Once it rained for 30 straight days. I slept in a slit trench one night and woke up with only my head on my helmet above water.”

He remembered one humorous pleasure. “In Belgium, 250 of our men walked naked under a long pipe of hot water with holes in it. At the end we had new uniforms waiting. The local farm women watched and laughed.”

The 462nd scored their first combat kill four days after landing at Normandy. After six weeks, Battery A had shot down three planes. The Battery had a crew of five: Sam, the defending machine gunner; the cannon gunner; the shell loader; the elevation man; and the azimuth man. Soon enough, Sam helped his crew shoot down a Nazi fighter, probably a Messerschmitt.

“One of the worst experiences I had was scanning the sky and watching five B-17s get blown out of the air. Had to turn my back. Couldn’t watch it. No parachutes.”

“My other job was a communications lineman and wire runner. I ran a 5-mile reel of wire from our gun to the Command Post. At 3 A.M. one morning, I took a shortcut across a field running my wire. I remained overnight at the CP, then returned the next day to my gun via that field. The sign said: ‘DANGER MINE FIELD!’ I sat down against the fence and threw up. From then on, I never cut corners and never ran wire alone. When they came up with battery-operated handheld phones, I said, ‘Thank you, Lord, no more wire, no more radios. Thank you, Lord, for that.’”

Sam recalled another adventure. “Once we had a rest camp near a brewery town. So we went looking for beer and found a keg; then tested it with our canteen cups. Neither one of us was able to speak; it took my breath away. Later I found it was Calvados apple brandy of 150 proof (75% alcohol) like bootleggers make.”

I asked, “Make any mistakes over there?” Sam chuckled. “I was a scavenger: I found some jars of canned fruit in an old farmhouse cellar and ate a jar of apples; and spent five days in the toilet. Also, got my eyes wind burnt while driving and watching, without goggles, for enemy planes to strafe us. I was blind for several days until my eyes healed.”

“At a rest camp in Belgium, a farmer went digging in his apple orchard and brought me a .32 pistol, rusty and corroded, wrapped in a rotting rag. It still worked. I was carrying it in my backpack when I got hit.”

In October of 1944, Sam and Battery A were ordered to a quiet sector in the Ardennes forest where, unknown to them, the Battle of the Bulge would soon begin.

Battery A had the mission to protect the 15th Field Artillery Battalion as they advanced behind the 2nd Infantry Division of the 1st Army, and Patton’s 3rd Army, against the German 7th Army and 6th Panzer Army.

During the Battle of the Bulge, the encircling Germans had trapped many American soldiers as they tried to get back to U.S. lines. On the second day of the battle, December 18, 1944, at 2:30 A.M., Sam told me, “I got blowed out of a foxhole with a hand grenade.”

Battery A was sleeping in an abandoned farmhouse near Saint Vith, Belgium. At 2 A.M., Sam went forward to relieve a guard on duty in a foxhole, watching the snowy woods for approaching enemy. He heard the sound of rocks coming down the road and shouted out the challenge of the day: but no response. Then a German potato masher grenade sailed past him and exploded, lifting him out of his foxhole.

The other G.I guard ran up and jumped on top of Sam, whispering, “Sam, are you hurt?” Sam answered, “I am now!”

Then the officers came running and asked Sam, “What color were their uniforms and what kind of guns were they carrying?” Sam answered, “Sir, it is 2:30 in the morning, black as the ace of spades, so how am I supposed to see the color of their uniforms?”

Other G.I.s lifted Sam out of a trench, then placed him face down on a stretcher across the hood of a Jeep, and drove him to a first aid station in a nearby house for stabilization by medics, then to the field hospital.

“When I was wounded, I never lost consciousness. I remember the medics counting out loud how many holes I had in my back, butt, and legs. Their grenades were designed to cripple you, to take you out of action. The Germans believed that would also take support people out of the fight.” He added, “The German machine guns were bolted down knee high to cripple us.” The Germans believed that one wounded man would reduce the total number of fighting Americans more than one dead G.I.

Sam remembers, after sixteen months of combat duty, “I like to think I saved my men sleeping in that house at the end of the road. I’ve been carrying metal every since.” He smiled and said, “I have a lot of fun with the shrapnel in my back and butt when I get X-rayed.”

The Sam told me, “If I did it again, I’d prefer KP.” Why such a curious answer, I wondered?

Sam said, “That old mess sergeant took care of me and gave me some good advice. He taught me one thing, ‘Son, when you challenge someone on guard duty, turn your head, never challenge straight.’ That night I challenged the German, I turned my head and that’s why the grenade went behind me. I turned my head to throw my voice away from me and I guess that’s what really saved me that night.”

Sam was evacuated to a hospital in France. “Nine months on my belly; no feeling below the waist. I was strapped to a bed and they cleaned my wounds every day. Then I went to England.”

“What was your great wish over there?” I asked. “My great wish in combat was to get it over with and go home. I saw the Statue of Liberty through a porthole. Then an ambulance took me to Fort Custer in Battle Creek, Michigan where I was honorably discharged as a Private First Class.”

“After ten months in hospitals, I was able to walk again, and then discharged in September, 1945 with a new uniform, $300, and a ticket home. I took a train south to Union Station, then a streetcar to my house in St. Louis, ditching my leg brace along the way, and walked into our house to surprise Laura. Coming home was fantastic.”

“Sam,” I asked, “What did you value about military service?”

“Discipline, respect for authority and other people. No one is different. It made me a better person and husband. I learned humility, comradeship, how to get along with people different from you, and to keep your eyes and ears open. The hardest thing I had to learn was taking orders.”

“What do you want remembered about you and your service?”

“Not much. I did what I had to do: did my job, came back.”

When we concluded our interview, Sam still had that look, that sparkle of freedom given and brought home from France and Belgium, an inner energy far surpassing the collection of German steel shrapnel in his body.

As I was heading home after the interview, I couldn’t help but reflect with awe at what Sam and the other 19-year-olds did for me and my future in 1944 when I was one year old. Thanks to them, I got to have a free boyhood and grownup life. This interview was my secret privilege to pass on Sam’s story to you and add a little polish to our national tradition of military service that ensures the freedom of future Americans. Across a generation, as generations before us, we are brother warriors who would do it all again if need be. To others who wonder why we Americans do what we do for them and for the world, that is the best explanation I know. I think my friend’s Uncle Sam Losh would agree.