Author's Name: Jay Harden

Title: "My Mother of All Letters"

Among other things, war brought to me the intensest of emotions.I left her one overcast and late September day in 1968 as I mounted the blue flight crew bus taking my bomb wing to the tarmac and a flight over The Pond to combat in Vietnam. It was an unceremonious farewell, so clumsy casual, hiding the deep and wonderful love that was our shared secret. I was gruffly brave and she never more shining, bright in the eyes, with that trademark embracing smile and a glowing beauty that still blinded me, the luckiest man in the universe. We tried to say our intimate goodbye the night before, but I was already withdrawing into my protective warrior shell, knowing well, as she did not, what I was about to do half a world away, although I had no idea how severely my actions would affect me—and us—for the rest of our too-short life together.

I lived many lifetimes in my months away, each one its own story worth telling. But one constant that bound those days together in one sane and blessed whole for me was her letters. She wrote me faithfully, constantly, and vitally, each her small gift of grace across the sea. Along with the audiotapes we exchanged, I heard from her, on average, every single day, although the military mail system in those days and my unpredictable movements to Guam, Thailand, and Okinawa made mail call feast or famine for me.

Some days I got nothing, and other days I got bundles of letters, pastel and faint of perfume. I must have told her the depth of joy those physical papers gave me, for certainly I told my crew. In fact, I gloated and soon learned the indiscriminate power that letters from home possess.

My bombardier, who sat to my left in the belly of the B-52, outranked me. I was the lowest of the low, a first lieutenant, even lower in status than the gunner, a grandfather sergeant with eight stripes, who had more wisdom than we five officers put together. After seven weeks or more, the bombardier had not received a single letter from his wife, no communication at all, no word of their young son. They were our neighbors back on Westover Air Force Base, Massachusetts, where we lived in housing so substandard and infested with termites that it would be condemned outside the base, but we felt fortunate anyway because we lived across from the 8th Air Force commanding general and that meant we got our shared street plowed first when the snows came, snows that made two Georgia peaches shrivel and gasp.

Lacking any letters, the bombardier tried to phone his wife long-distance. Then he tried MARS, the Military Affiliate Radio System, a 20-year-old amateur shortwave network of phone patches operated by volunteer ham radio operators primarily for morale and personal emergencies. He still could not reach her. Slowly he became absolutely frantic within. I watched his emotional balance deteriorate. Every possible night he would leave our Bachelor Officer Quarters to go drinking, then stumble back, turn on the shower, and curl up under his personal waterfall in the corner. By morning, and by miracle to me, he appeared sober and took to the sky with the rest of us, adding to my increasing secret anxiety about the constant grim work with him I was bound by duty and promise to do.

But every plump letter I received from Carolyn—a beautiful rolling sound in my mind that I still hear—soothed my accumulating stress and erased every grimy line on my face. Her letters meant more joy to me than any quantity of gold. They, innocent and without intention, preserved my emotional heart. Her unconditional love, her acceptance, and her non-judgment of me, a young killer in the making, to this day still feeds my soul though she is gone. No one else can know the depth of that gift, not even she, and that is why I need to record this story of her treasured writing.

One night, my bombardier returned to quarters with his right hand immobilized, the same hand needed to aim the crosshairs on our bomb runs. The flight surgeon had inserted a stainless steel pin through his pinky fingernail and bone. The pin was under tension with rubber bands to somehow align a fracture, I suppose. That evening, the painkillers wore off and he was in unremitting agony.

I did not see him again until morning. The scary contraption was gone, replaced by a conventional plaster cast. To my amazement, he was not grounded and we flew another combat mission the next day. I learned later that he had been in a fight with some guy in civilian clothes who ducked his punch, causing him to crack a concrete urn of flowers behind. Even later, I learned that the other guy was an enlisted man, but I never heard if the captain was court-martialed.

Eventually, after about one-third of our combat tour, the bombardier heard from his wife. All I learned secondhand was that she and her girlfriend had taken off for fun in Cape Cod, whatever that implied. And every day that I picked up my letter or bundle of letters, my ecstasy must have wounded him again and again.

I remember exactly when I got my mother of all letters. The date was October 20, 1968. Five days earlier I had hopped a ride on a bombing mission from Andersen Air Force Base, Guam and landed at Kadena Air Base, Okinawa, where I joined a new B-52 crew. We flew our first mission together the next day on my 25th birthday and landed on Guam. (Only four weeks later, that very aircraft aborted takeoff with a full bomb load and blew up off the end of the Kadena runway, killing two. Against all logic, I felt spared.)

Those longer sorties from one base to another were particularly draining, but all of them repeated the same emotional sequence for me: growing anxiety while roaring inbound to Vietnam with eight lungs breathing righteous fire and 60,000 pounds of bombs; next, the sensational adrenaline rush for seven minutes on the bomb run when time melts with your mind in a thrilling, private taffy flow; then the temporary liberation of tension after bombs away and steep breakaway turn realizing we beat the enemy yet again. These extreme emotions were followed by the intolerable stupor and exhaustion of flying across thousands of miles of Pacific Ocean, only to be compounded by my deep navigation doubt of finding a sneaky island only 40 miles long, and finally ending with the safe landing of our massive beast on 10,000 feet of undulating runway, while in the back of my mind was the Marianas Trench below the 600-foot cliff at the end of the runway, an abyss that had already swallowed a completely loaded combat B-52 and crew without a trace.

That day’s bombing mission left me worn-out and impatient beyond my usual self. I was trapped in a body screaming with every step for rest and relief after over 12 hours of relentless demands by a dominating metal mistress.

After the tedious, irritating, but necessary, debriefings, I stumbled to the mailroom and clutched a single, unusually thin, and lumpy letter, and another later dated one, my prizes for surviving yet another ever darker dance with death seven miles above a deceptive lush green jungle.

This time on Guam we were randomly assigned to two-man rooms in the Visiting Officer Quarters. I sat cross-legged on my bunk at the front of the room, back to the door, anticipating the comfort I held in my hand, my heavy, salt-encrusted flying boots still zipped to my feet, in my stinky, greasy, sweat-stained, olive flight suit, bulging with the hanging weight of war tools: pens, pencils, checklists, plotter, dividers, orange survival switchblade, gloves, keys, wallet, and my life-saving E-6B dead reckoning computer (really a simply ingenious circular slide rule on steroids). Somewhere beside the bed, I had dumped my brain bucket and flight bag of maps, star tables, and other navigation stuff I have since forgotten.

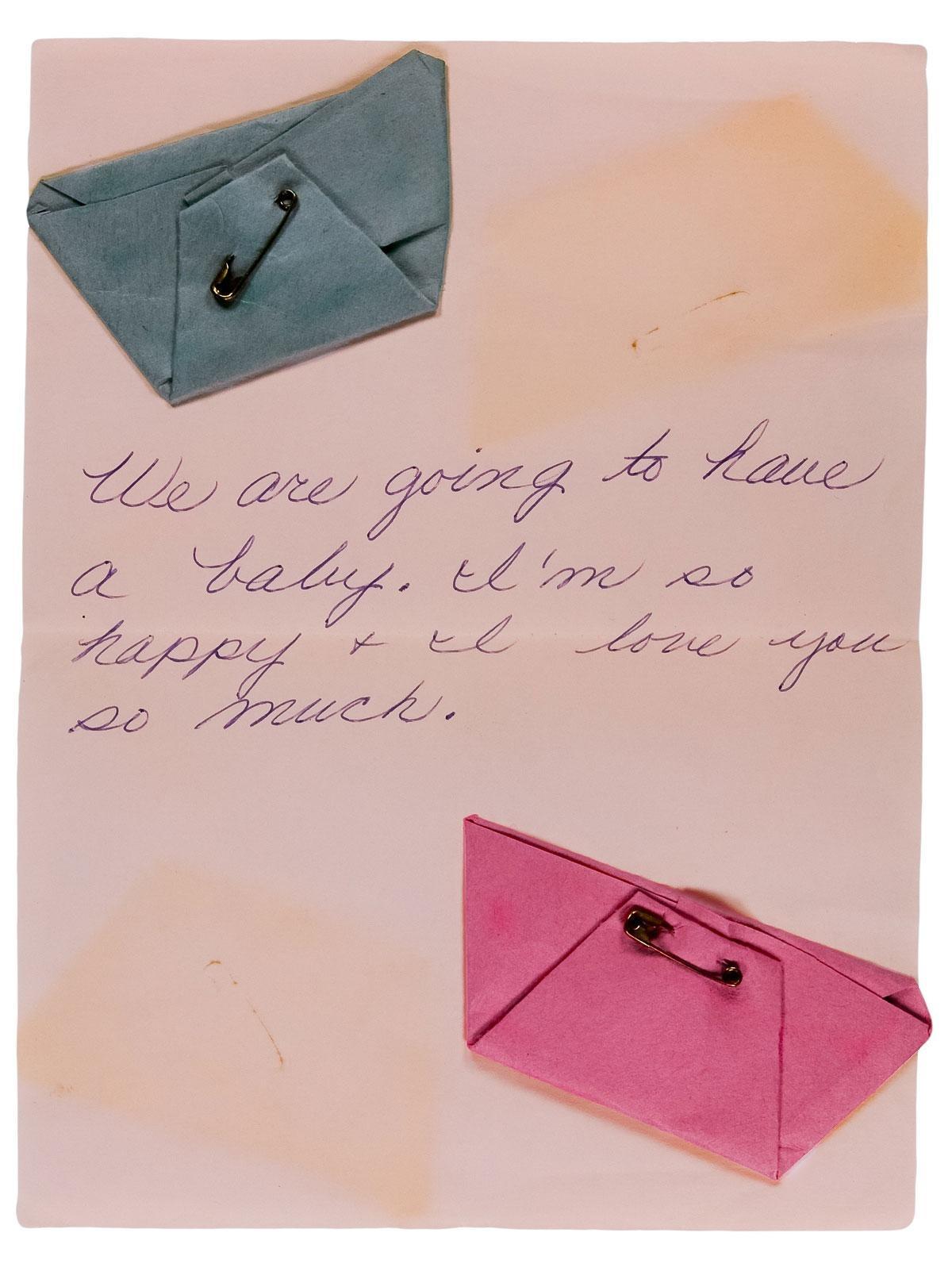

The first treasure in my hand felt uniquely odd. In an anxious, fumbling caress I opened it, pulling out a single sheet of pastel with smaller blue paper attached in the upper left corner and pink in the opposite. My heart cranked up to racing. Could it be? Could our future be coming true?

Each corner was a folded piece of construction paper, familiar visual fare to any man in love with an enthusiastic elementary school teacher. Each color had been cut into a triangle and the corners folded in, overlapping each other into a suggestive shape. In each center was a shiny, petite brass safety pin.

Now I was in a daze, softly trembling with anticipation, breathing rapidly and happily, and well seasoned by fatigue from the subsiding vibrations of aeronautical intimacy with my 400,000-pound metal mama.

There in the middle of the page, in her confident, generous, and open swirls, she had simply handwritten these exquisite, echoing words:

We are going to have a baby.

I’m so happy & I love you so much.

These were the only words of hers in my mother of all letters, and no more were needed.

That moment, the entire universe stopped for me, in our honor. The rest of you did not notice that fleeting beat, but I can recall it at will even now. And when I do, I smile into the wind.

There I sat on a small tropic island, breezy in the setting sun, a place coconuts and coral call home, where it rains a little every day. There I sat on a drab and itchy G.I. blanket and just wept the first, best joy I ever knew. There I sat alone with her presence in paper, lonely not at all.

In that superb and shining moment, I was innocent of destruction and killing, whole, perfect, and unstained.

In that moment, hope conquered death.

In that moment, I knew I would survive my war for my woman and my child.

In that moment, my passion for living outshined the darkest deeds of mine against my fellow human beings.

In that moment, I fell in love with a little girl I had yet to meet and with my grownup girl yet again.

In that moment, thanks to the mother of all my letters and the mother I had made, I became a father and a man reborn.

Suddenly the door opened and an unknown officer entered, my roommate for the night. I put my head down, arms around my knees. He walked past and threw his flight gear on his bed, then sat down. After a pause, he asked me if anything was wrong. I simply turned my back to him and kept crying, unable to explain or share my ineffable happiness with another stranger.

Soon enough, I tore through the letter that followed, finding more of her lovely words:

Oh how I wish we could rejoice together.

We are lucky to have been given the opportunity to raise a child.

I will try to be brave and good so our baby will have a happy time inside me.

I feel like a little bird with a huge wonderful song to sing.

Please take care of yourself for the daddy must be in top shape to play, read, love, and help the baby.

The following morning, I rushed to the Officers’ Club and called Carolyn long distance at her parents’ house, 12 hours past my time. She picked up the phone. And the beauty of her hello silenced me so I could not speak. Feelings as grand and pure as chocolate flooded me, triggered by her soothing Southern lilt and words of tender admiration for her man, her private hero. Life flowed back and forth through those wires, now embracing a third one: the most beautiful telephone conversation I ever had.

She was fine. The baby was fine. And in her voice was something new: a richness; a beginning of the wisdom we needed to guide a fresh baby into a beautiful world. That woman and that child in that moment gave me a zest and strength I had never known and helped me through my war.

There were other letters from my war days, of course, and audiotapes. I did not write her in return nearly as many times for reasons she did not understand and never could. But she forgave me anyway for my omissions and the accumulating wounds of war to my soul.

I kept all her letters in the basement, in a box plainly labeled. Over the years before her unexpected death at 42, she often asked me to throw her letters away. One day in anger I told her I would, but I destroyed only the box and secretly repackaged and moved the letters elsewhere, put them out of my mind along with my worst memories of Vietnam, and eventually forgot they existed.

Some years after she died and we moved away, a friend got me interested in genealogy and I started family research at the Library of Congress and the National Archives. In time I stumbled across the Civil War letters of my great-grandfather in a Georgia library.

Then I remembered Carolyn's letters to me in Vietnam. In my search for them, I also found my letters to her she had hidden away that I thought lost, and my mother of all letters, the one so short, so simple, and so treasured from the mother of my children to me.

I insisted we name our baby after her, and when that little girl grew up, she did the same with her daughters.